COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT Evaluation of Directive 2009/81/EC on public procurement in the fields of defence and security Accompanying the document Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the implementation of Directive 2009/81/EC on public procurement in the fields of defence and security, to comply with Article 73(2) of that Directive - Hoofdinhoud

Contents

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels, 30.11.2016

SWD(2016) 407 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

Evaluation of Directive 2009/81/EC on public procurement in the fields of defence and security

Accompanying the document

Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the implementation of Directive 2009/81/EC on public procurement in the fields of defence and security, to comply with Article 73(2) of that Directive

{COM(2016) 762 final}

Contents

-

1.Introduction

-

2.Background

2.1.Government expenditure on defence and security

2.1.1.Estimate of defence procurement expenditure

2.1.2.Procurement of defence equipment

2.1.3.Outlook in defence and security expenditure

2.2.The rationale for Directive 2009/81/EC

2.2.1.The specific problem to be addressed by Directive 2009/81/EC

2.2.2.General and specific objectives

2.2.3.The operational objective and the main features of the Directive

2.3.Baseline: the situation before Directive 2009/81/EC

2.3.1.Regulatory patchwork

2.3.2.EU-wide publication of business opportunities

2.3.3.Cross-border awards

-

3.Evaluation questions

-

4.Method

4.1.OJ/TED data

4.2.Other data sources

4.3.Stakeholders consultations

4.4.Methodological issues and data availability

-

5.Implementation state of play

5.1.Transposition

5.1.1.The transposition process (August 2011-May 2013)

5.1.2.Technical analysis of transposition measures

5.1.3.Offsets / industrial return regulations in the context of transposition

5.2.Compliance activities concerning individual procurement cases

5.3.Uptake of the Directive

5.3.1.Defence and security procurement under the Directive

5.3.2.Defence and security procurement under the civil procurement Directives

-

6.Answers to the evaluation questions

6.1.Effectiveness

6.1.1.Competition, transparency and non-discrimination

6.1.2.Use of exemptions

6.1.3.Member States security concerns

6.1.4.Changes in the industrial base (EDTIB)

6.1.5.Conclusions on effectiveness

6.2.Efficiency

6.2.1.Costs of procedures

6.2.2.Costs compared to benefits

6.2.3.Administrative burden

6.2.4.Conclusions on efficiency

6.3.Relevance

6.3.1.The objectives of the Directive

6.3.2.New developments after the adoption of the Directive

6.3.3.Conclusions on relevance

6.4.Coherence

6.4.1.Internal coherence

6.4.1.Coherence with the framework of EU public procurement law

6.4.2.Directive 2009/43/EC

6.4.3.CSDP and a European capabilities and armaments policy

6.4.4.Cooperation in defence procurement

6.4.5.Conclusions on coherence

6.5.EU added value

-

7.Conclusions

-

8.Annexes

Annex I – Procedural information

Annex II – Stakeholder consultations

Annex III – Methods and analytical models

Annex IV – Complementary data

-

9.Bibliography

Glossary

ASD |

AeroSpace and Defence Industries Association of Europe ( http://www.asd-europe.org/home/ ) |

Baseline Study |

“Openness of Member States’ defence markets” by Europe Economics for the Commission services in November 2012 |

BIS |

Bureau of Industry and Security of the U.S. Department of Commerce, ( https://www.bis.doc.gov/ ) |

civil procurement Directives |

Directive 2004/18/EC on the coordination of procedures for the award of public works contracts, public supply contracts and public service contracts and Directive 2004/17/EC coordinating the procurement procedures of entities operating in the water, energy, transport and postal services sectors |

CPV |

Common Procurement Vocabulary; Commission Regulation (EC) No 213/2008 of 28 November 2007 amending Regulation (EC) No 2195/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Common Procurement Vocabulary (CPV) and Directives 2004/17/EC and 2004/18/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on public procurement procedures, as regards the revision of the CPV |

CSDP |

Common Security and Defence Policy |

Directive |

Directive 2009/81/EC on the coordination of procedures for the award of certain works contracts, supply contracts and service contracts by contracting authorities or entities in the fields of defence and security, and amending Directives 2004/17/EC and 2004/18/EC |

DG GROW |

Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs ( http://ec.europa.eu/growth/index_en ) |

EDA |

European Defence Agency ( https://www.eda.europa.eu/ ) |

EDEM |

European Defence Equipment Market |

EDTIB |

European Defence Technological and Industrial Base |

Evaluation Roadmap |

Roadmap on the Evaluation of Directive 2009/81/EC ( http://ec.europa.eu/smart-regulation/roadmaps/docs/2016_grow_031_evaluation_defence_procurement_en.pdf ) |

FMS |

Foreign Military Sales ( http://www.dsca.mil/programs/foreign-military-sales-fms ) |

Impact Assessment |

Commission Staff Working Document Annex to the Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the coordination of procedures for the award of certain public works contracts, public supply contracts and public service contracts in the fields of defence and security ( http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/publicprocurement/docs/defence/impact_assessment_en.pdf ) |

M&A |

Mergers and acquisitions |

NATO |

North Atlantic Treaty Organization ( http://www.nato.int/ ) |

OCCAR |

Organisation Conjointe de Coopération en matière d'Armement ( http://www.occar.int/185 ) |

OJ/TED |

Tenders Electronic Daily is the online version of the 'Supplement to the Official Journal of the EU, dedicated to European public procurement ( http://ted.europa.eu/ ). |

PwC Study |

“Public procurement in Europe, Cost and effectiveness” done by PwC, Ecorys and London Economics, for the Commission services in March 2011 http://bookshop.europa.eu/en/public-procurement-in-europe-pbKM3113708/ |

SCAP Study |

“Support to the implementation of the Supply Chain Action Plan” by IHS Global Limited for EDA |

SBS |

Structural Business Statistics |

Technopolis Study |

“Evaluation of Directive 2009/43/EC on the Transfers of Defence-Related Products within the Community” by Technopolis group for the European Commission |

VEAT |

Voluntary ex-ante transparency notice |

-

1.Introduction

The legal basis for this evaluation is Article 73(2) of Directive 2009/81/EC (the Directive), which states that “the Commission shall review the implementation of this Directive and report thereon to the European Parliament and the Council by 21 August 2016. It shall evaluate in particular whether, and to what extent, the objectives of this Directive have been achieved with regard to the functioning of the internal market and the development of a European defence equipment market and a European Defence Technological and Industrial Base, having regard, inter alia, to the situation of small and medium-sized enterprises. Where appropriate, the report shall be accompanied by a legislative proposal”.

The purpose of the evaluation is, therefore, to assess the functioning of the Directive and, to the extent possible, its impact on the market and on the industrial base. As to the scope, the whole of the Directive is subject to evaluation. Time-wise, the evaluation covers the period from the transposition of the Directive (2011) until the end of 2015. The situation before the transposition of the Directive is taken into account as baseline. Given the short time that has elapsed since the transposition deadline, and even more since its actual transposition by Member States, it can be expected that the conclusions about the Directive’s impact on the European Defence Equipment Market (EDEM) and, especially, on the European Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB) would be very difficult to reach 1 . In that context, the evaluation assesses whether we are on track to meet the objectives set by the Directive. From a geographical point of view, the evaluation focuses on the 28 Member States of the EU and 2 EEA 2 countries (Norway and Iceland).

-

2.Background

This section seeks to provide background information that is essential for the evaluation of the Directive. This includes, first and foremost, data on Member States’ expenditure on defence and security and, in particular, on procurement. It also provides a brief description of the Directive and its different components, its objectives and the problems it was intended to solve; the key source in this respect is the Impact Assessment that accompanied the Commission’s proposal (the Impact Assessment) 3 . The background section also includes a description of the baseline, i.e. what the situation was like before the adoption of the Directive.

2.1.Government expenditure on defence and security

Government expenditure on defence and security in Europe accounts for a significant share of the nations’ GDP and the total public spending. For example, the guideline agreed by NATO Allies state that at least 2% of GDP should be allocated to defence spending. Meanwhile, according to the recent data for the European NATO countries 4 , defence expenditure in 2015 accounted for 1.45% of their GDP 5 . Similar range of estimates is provided by the European Defence Agency (EDA), which reports that defence expenditure of the 27 EDA Member States 6 in 2014 was around 1.42% of their GDP 7 and equalled roughly 195 billion EUR 8 .

According to Eurostat COFOG classification, defence expenditure (GF02) 9 equalled 1.3% of GDP for the EU-28 and amounted to roughly 187.4 billion EUR in 2014 (or 192.8 billion EUR, if the EEA countries were included). The highest levels of total expenditure on defence were found in Greece (2.7% of GDP), followed by the United Kingdom (2.2 % of GDP) and Estonia (1.8% of GDP), whereas Luxembourg (0.3 % of GDP), Ireland (0.4 % of GDP) as well as Austria and Hungary (both 0.6 % of GDP) reported comparatively low expenditure on defence 10 .

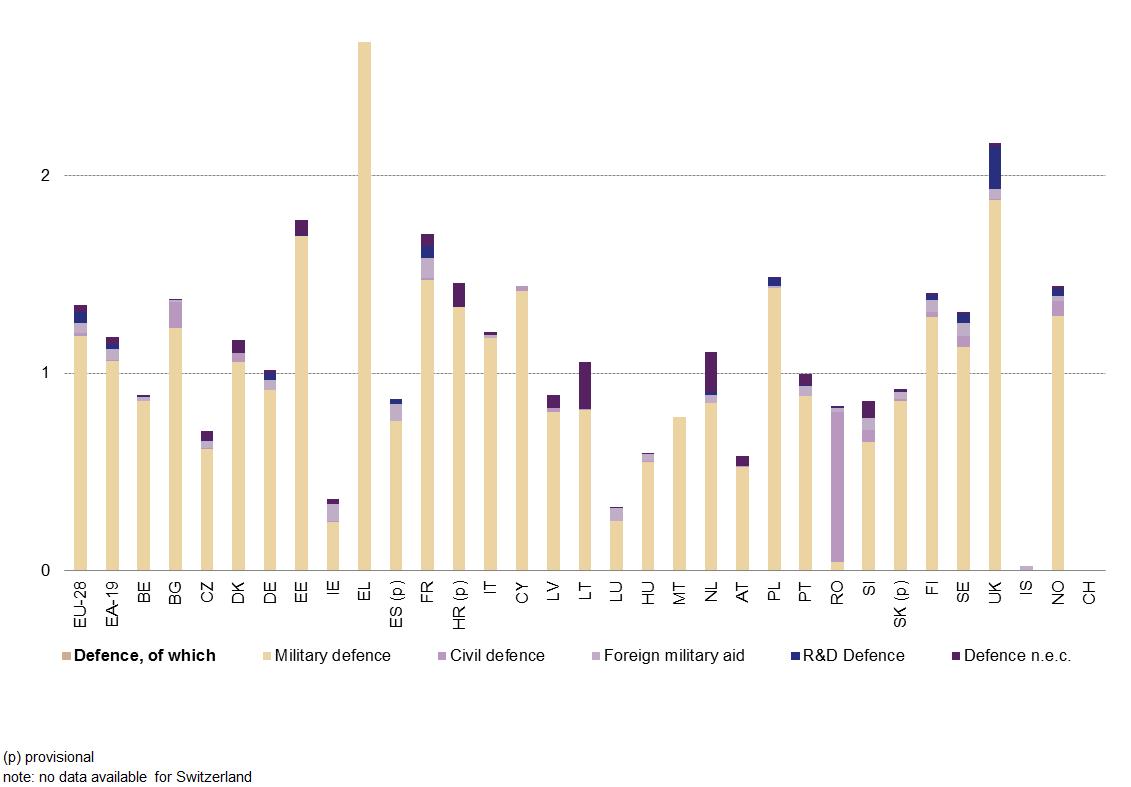

Figure 1: General government expenditure on defence in 2014 [% of GDP]

Source: Eurostat, http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Government_expenditure_on_defence

As presented on the graph above, in all countries except for Romania, the major part of the total general government expenditure on defence (GF02) in 2014 was spent under military defence (GF0201) 11 . Eurostat estimates that military defence expenditure in the EU accounted for around 1.2 % of GDP of EU-28 in 2014, which in monetary terms equalled roughly 165.7 billion EUR ( Table 1 ). If the EEA counties were added, the total would increase to roughly 170.6 billion EUR.

Table 1: Government expenditure on military defence [value in million EUR]

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

|

Belgium |

3 402.8 |

3 425.4 |

3 444.8 |

3 550.3 |

3 445.9 |

Bulgaria |

630.9 |

447.0 |

420.6 |

491.1 |

525.2 |

Czech Republic |

1 332.0 |

1 272.5 |

1 139.1 |

1 031.1 |

950.9 |

Denmark |

3 006.7 |

3 184.0 |

3 422.8 |

3 248.5 |

2 752.3 |

Germany |

24 720.0 |

25 771.0 |

27 145.0 |

27 064.0 |

26 639.0 |

Estonia |

240.3 |

234.3 |

306.6 |

327.5 |

337.9 |

Ireland |

476.6 |

475.4 |

463.1 |

459.1 |

468.0 |

Greece |

6 069.0 |

4 955.0 |

4 610.0 |

3 878.0 |

4 758.0 |

Spain |

10 133.0 |

9 622.0 |

8 546.0 |

8 721.0 |

7 889.0 |

France |

31 349.0 |

30 874.0 |

32 020.0 |

32 309.0 |

31 341.0 |

Croatia |

618.5 |

663.2 |

620.8 |

566.3 |

573.5 |

Italy |

20 668.0 |

21 299.0 |

19 816.0 |

18 486.0 |

19 009.0 |

Cyprus |

401.1 |

356.8 |

338.1 |

282.7 |

246.2 |

Latvia |

168.1 |

186.1 |

174.9 |

185.8 |

189.4 |

Lithuania |

233.6 |

242.3 |

254.5 |

261.2 |

296.9 |

Luxembourg |

185.8 |

149.8 |

135.1 |

124.7 |

121.7 |

Hungary |

1 113.0 |

1 008.9 |

677.1 |

628.6 |

570.9 |

Malta |

50.4 |

56.0 |

50.6 |

49.1 |

62.9 |

Netherlands |

6 047.0 |

6 368.0 |

5 715.0 |

5 875.0 |

5 613.0 |

Austria |

1 727.8 |

1 749.2 |

1 708.5 |

1 828.8 |

1 727.8 |

Poland |

5 381.9 |

5 628.1 |

5 421.7 |

6 258.2 |

5 872.1 |

Portugal |

3 521.9 |

2 237.7 |

1 606.5 |

1 648.6 |

1 532.4 |

Romania |

952.7 |

52.8 |

48.5 |

53.6 |

66.7 |

Slovenia |

452.7 |

357.6 |

315.6 |

261.7 |

242.8 |

Slovakia |

573.3 |

601.7 |

601.6 |

626.6 |

650.0 |

Finland |

2 459.0 |

2 470.0 |

2 745.0 |

2 768.0 |

2 640.0 |

Sweden |

4 398.3 |

4 879.4 |

4 987.2 |

5 482.6 |

4 874.0 |

United Kingdom |

38 265.9 |

38 035.2 |

41 427.1 |

39 341.3 |

42 295.2 |

Total EU-28 |

168 579.3 |

166 602.4 |

168 161.8 |

165 808.4 |

165 691.7 |

Iceland |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

Norway |

4 249.5 |

4 900.3 |

4 879.0 |

4 842.6 |

4 867.6 |

Total EEA |

4 249.5 |

4 900.3 |

4 879.0 |

4 842.6 |

4 867.6 |

EU-28 and EEA |

172 828.8 |

171 502.7 |

173 040.8 |

170 651.0 |

170 559.3 |

Source: Eurostat, general government expenditure by function (COFOG) [gov_10a_exp]

The total general government expenditure on military defence can be further disaggregated into specific national accounts components (ESA 2010), such as personnel costs (e.g. wages, salaries as well as employers' social contributions) and, among other, the cost items that can serve as a proxy for the estimate of the value of public procurement linked to the military defence function of the general government, as presented in the following section.

2.1.1.Estimate of defence procurement expenditure

The estimates of the military defence procurement expenditure by general government of EU-28 and EEA countries are presented in Table 2 below. This is the closest possible proxy of the maximum potential value of defence procurement expenditure, irrespective of whether the Directive is legally applicable to specific purchases. It is, therefore, the main expenditure estimate used in this evaluation, to assess the extent of application of the Directive, including the volume of exempted procurement (see in particular Sections 5.3.1.1., 6.1.1.1., and 6.1.2.1.).

In line with the methodology applied to calculate the total expenditure on works, goods and services for the general government in civil procurement 12 , the estimate was based on the following aggregates extracted from COFOG classification for military defence (GF0201) by the general government: ‘gross fixed capital formation’ 13 and ‘intermediate consumption’ 14 . ‘Social transfers in kind – purchased market production’ 15 , which are added to the estimate of government procurement expenditure in the civil sector were equal to zero in all countries in the military defence sector 16 .

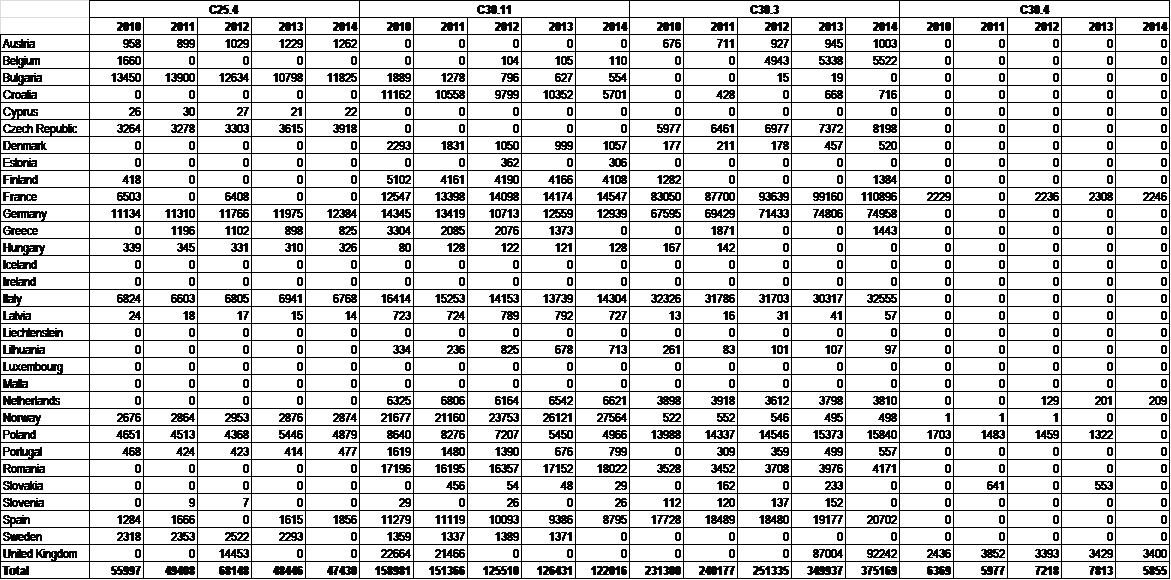

Table 2: Government procurement expenditure on military defence [value in million EUR]

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

|

Belgium |

768.0 |

771.6 |

745.9 |

812.1 |

828.7 |

Bulgaria |

294.2 |

119.6 |

108.1 |

123.9 |

164.6 |

Czech Republic |

762.3 |

693.4 |

563.0 |

483.9 |

408.2 |

Denmark |

1 601.2 |

1 709.5 |

1 960.5 |

1 835.1 |

1 478.8 |

Germany |

12 114.0 |

13 229.0 |

15 044.0 |

14 919.0 |

14 582.0 |

Estonia |

158.7 |

146.1 |

208.7 |

217.0 |

217.0 |

Ireland |

91.8 |

85.8 |

79.0 |

78.3 |

86.1 |

Greece |

2 591.0 |

1 564.0 |

1 302.0 |

1 012.0 |

1 571.0 |

Spain |

3 698.0 |

3 425.0 |

2 421.0 |

2 618.0 |

1 892.0 |

France |

14 376.0 |

13 696.0 |

14 504.0 |

15 040.0 |

13 910.0 |

Croatia |

181.9 |

233.0 |

215.6 |

197.8 |

234.0 |

Italy |

6 388.0 |

6 597.0 |

5 239.0 |

4 061.0 |

4 889.0 |

Cyprus |

177.3 |

122.1 |

102.9 |

43.8 |

36.0 |

Latvia |

97.4 |

95.6 |

68.0 |

77.9 |

94.3 |

Lithuania |

71.4 |

82.0 |

87.4 |

89.4 |

115.7 |

Luxembourg |

0.0 |

79.4 |

60.9 |

47.3 |

44.0 |

Hungary |

417.4 |

305.5 |

336.5 |

307.9 |

258.9 |

Malta |

12.0 |

18.0 |

14.1 |

11.4 |

24.3 |

Netherlands |

2 363.0 |

2 715.0 |

1 961.0 |

2 078.0 |

1 783.0 |

Austria |

528.4 |

564.4 |

538.7 |

671.2 |

582.3 |

Poland |

2 064.0 |

2 420.0 |

2 130.4 |

2 738.7 |

2 249.5 |

Portugal |

1 809.0 |

673.7 |

401.6 |

378.5 |

364.3 |

Romania |

8.0 |

6.3 |

5.4 |

5.3 |

4.7 |

Slovenia |

197.2 |

107.4 |

78.4 |

58.3 |

51.8 |

Slovakia |

198.7 |

218.6 |

207.8 |

208.9 |

223.2 |

Finland |

1 490.0 |

1 467.0 |

1 719.0 |

1 759.0 |

1 622.0 |

Sweden |

2 876.0 |

3 222.2 |

3 261.5 |

3 576.0 |

3 058.0 |

United Kingdom |

23 554.5 |

23 193.3 |

26 003.0 |

25 322.0 |

28 200.6 |

Total EU-28 |

78 889.4 |

77 560.5 |

79 367.4 |

78 771.7 |

78 974.0 |

Iceland |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

Norway |

2 493.6 |

3 012.4 |

2 830.6 |

2 819.0 |

2 761.2 |

Total EEA |

2 493.6 |

3 012.4 |

2 830.6 |

2 819.0 |

2 761.2 |

EU-28 and EEA |

81 383.0 |

80 572.9 |

82 198.0 |

81 590.7 |

81 735.2 |

Source: Eurostat, general government expenditure by function (COFOG) [gov_10a_exp]

As presented in Table 2 , in 2014 the largest budgets were at the disposal of the UK military sector (around 28 billion EUR), followed by Germany and then France (14.5 billion EUR and 13.9 billion EUR per year respectively). The disproportionately low value of military defence expenditure for Romania can be most probably explained by the fact that, in contrast to other countries, significant amounts relating to civil defence were reported by Romania (e.g. 0.8% of GDP in 2014).

The overall value of defence procurement expenditure by general government by the 28 EU Member States and EEA countries remained stable over the investigated period of time, ranging between 81 to 82 billion EUR per year. Neither has it changed significantly since the same analysis was carried out in the Impact Assessment - the average annual defence procurement expenditure in 2000-2004 calculated for EU-25 Member States was estimated at roughly 79 billion EUR 17 (not adjusted for inflation).

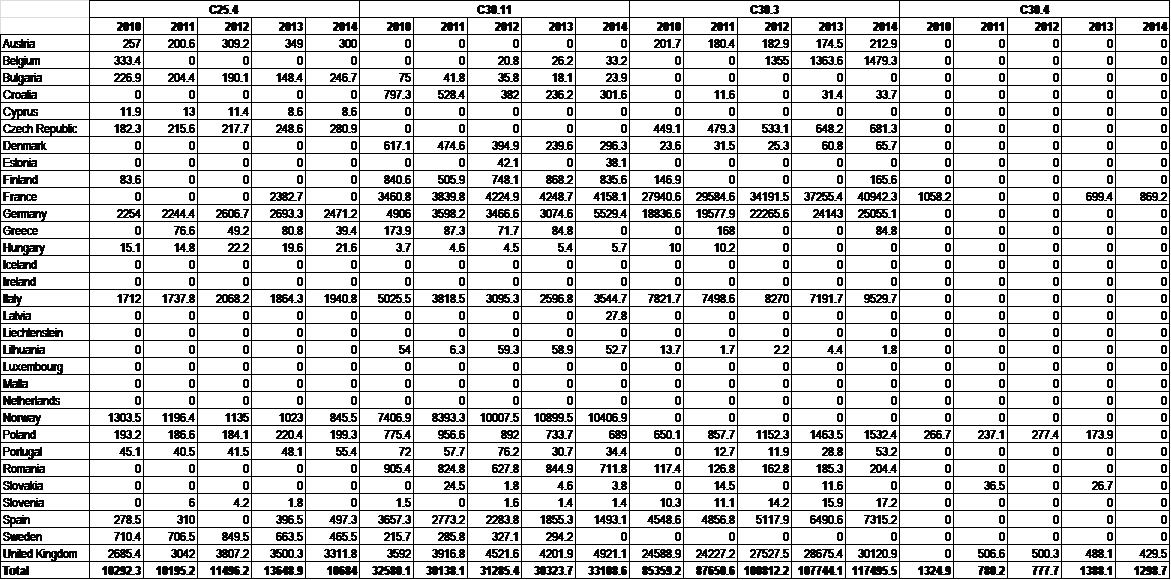

2.1.2.Procurement of defence equipment

The overall value of military defence procurement expenditure, as presented in Section 2.1.1 above, was estimated based on the data provided by Eurostat (COFOG). Unfortunately, this source of data does not allow obtaining more detailed breakdowns within the selected functions of government. In particular, components which could serve as comparators of the three procurement contract types (i.e. works, goods and service contracts) are not available in COFOG.

However, the expenditure on military equipment, which constitutes a fraction of the total defence procurement expenditure, is estimated by EDA and NATO. NATO divides defence expenditure into four main categories: equipment 18 , personnel 19 , infrastructure 20 and other 21 , while the EDA recognises the following breakdowns under the total defence expenditure: personnel, investment (equipment procurement and R&D), other expenditure (including infrastructure/construction), operation and maintenance. The EDA estimate of the value of defence equipment procurement, as presented in below, covers: the national defence equipment procurement, European collaborative defence equipment procurement and other collaborative defence equipment procurement.

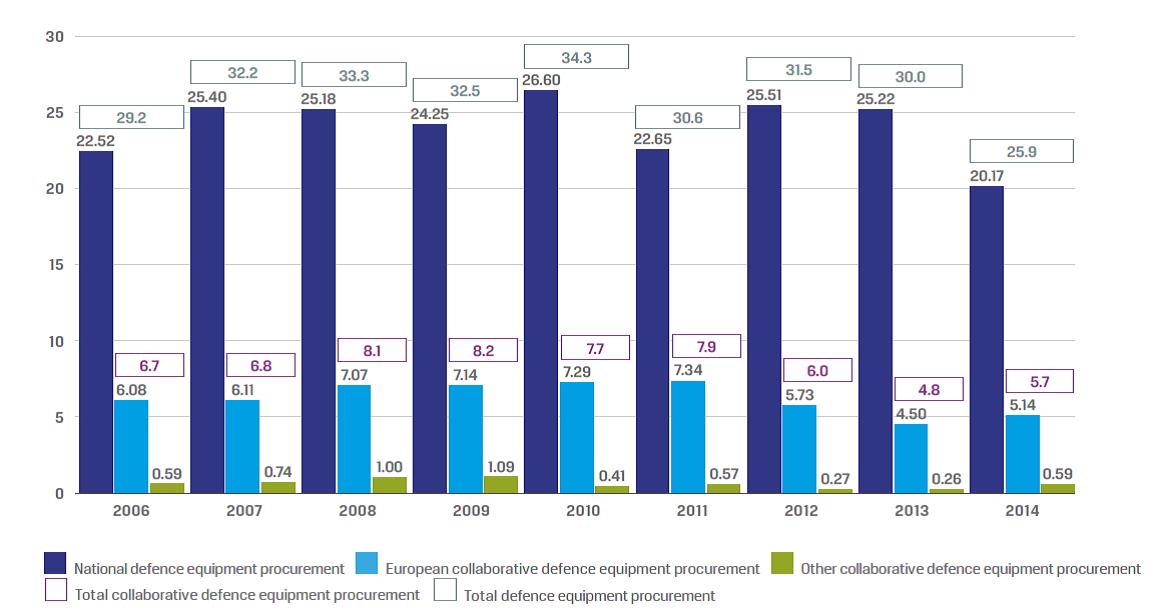

Figure 2: Defence equipment procurement [value in billion EUR]

Source: EDA, Defence Data 2014, http://www.eda.europa.eu/docs/default-source/documents/eda-defencedata-2014-final

The total defence equipment procurement expenditure reported by 27 EDA countries, accounted for nearly 30 billion EUR in 2013 and roughly 25.9 billion EUR in 2014. National defence equipment procurement was equal to around 20.2 billion EUR in the last year for which data was available (2014). As previously explained, the value of military equipment acquired in a given year constitutes a fraction of the total defence procurement expenditure, but it also constitutes the part of public spending that would be the most appropriate to serve as a denominator when evaluating the publication rate for the procurement of goods under the Directive.

2.1.3.Outlook in defence and security expenditure

Although defence spending has generally been decreasing since the end of the Cold War, there are multiple indications that due to recent changes in the geopolitical climate mainly driven by the terrorist threat, and deteriorating relations with Russia following the annexation of Crimea, the downward trend may reverse in the nearest future. In the NATO Annual Report 2015, it was noted that ‘in 2015, there was real progress toward fulfilling the commitment made in Wales. The first aim of the Wales pledge is to stop the cuts to defence spending: 19 countries are expected to have met this aspect of their commitment in 2015’ and ‘In 2015, 16 NATO members not only stopped the cuts to their defence budgets but increased their defence spending in real terms. Twelve of these countries are forecast to have increased their defence spending as a percentage of GDP in 2015’. As far as year 2016 is concerned, the signs of the new trend have recently also appeared via media coverage: according to Jens Stoltenberg NATO Secretary General ‘The forecast for 2016, based on figures from allied nations, indicates that 2016 will be the first year with increased defence spending among European allies for the first time in many, many years’. The latter was confirmed in a NATO Press Release of 4 July 2016 22 .

This trend may have an impact on the amount of defence procurement expenditure and, therefore, on the application of the Directive in the future.

2.2.The rationale for Directive 2009/81/EC

This section seeks to set out, on the basis of the Impact Assessment, the rationale for the EU intervention, i.e. the adoption of the Directive 2009/81/EC. The Directive regulates public procurement procedures for the award of certain works, supply and service contracts in the fields of defence and security. In essence, it provides that defence and sensitive security contracts, which fall within its scope of application, are not excluded, and whose value is above certain thresholds 23 , have to be awarded following competitive tendering procedures based on the principles of transparency and equal treatment.

Prior to the Directive, the award of such public contracts fell within the scope of Directives 2004/18/EC or 2004/17/EC (the civil procurement Directives), subject to the relevant Treaty-based derogations, in particular Article 346 TFEU (Article 296 TEC before 2009) 24 , and to the “secrecy” exclusions 25 .

2.2.1.The specific problem to be addressed by Directive 2009/81/EC

The specific problem identified in the Impact Assessment 26 – was that many Member States used Article 296(1)(b) TEC (now Article 346 (1)(b) TFEU 27 ) extensively, exempting almost automatically the procurement of military equipment from EU public procurement rules. Similarly, Member States exempted sensitive security contracts systematically on the basis of Article 296(1)(a) and/or Article 14 of Directive 2004/18/EC 28 . Derogations which should have been the exception according to the Treaty and the case law of the Court of Justice were, in practice, the rule 29 .

In the fields of defence and security, EU public procurement rules (Directives 2004/18/EC and 2004/17/EC) were rarely applied in practice. As result, most defence and security contracts were awarded on the basis of diverse national rules and administrative practices. This often led to a regulatory patchwork which was hindering the establishment of a common European defence equipment market and to non-compliance with the principles of the Treaty, in particular the fundamental freedoms of the internal market and the principles of non-discrimination and transparency, including the development of “buy-national practices”.

The main cause of the problem was deemed to lie in the general structure of EU civil public procurement rules (Directives 2004/18/EC and 2004/17/EC), which failed to address the specificities of defence and sensitive security procurement. These specificities were: the high degree of complexity, which calls for flexibility, and the special needs to ensure security of supply and the protection of classified information (security of information) 30 .

2.2.2.General and specific objectives

Together with the other elements of the so-called “defence package” that was proposed in 2007 31 , the Directive seeks to support the establishment of an open and competitive EDEM. This is expected to benefit both the supply and the demand side: European companies should obtain a larger “home” market, and competition should help public purchasers to get best value for money, thus saving scarce financial resources 32 .

A more open, competitive and efficient market should help suppliers to achieve economies of scale, optimise production capacity and lower unit production costs, thus making European products more competitive on the global market. This should, in turn, strengthen the competitiveness of European defence industry, by fostering consolidation across national boundaries, helping to reduce duplication, and enhancing industrial specialisation. Indeed, the gradual establishment of the EDEM is essential for a strong EDTIB that can provide the military capabilities that Member States need 33 . The Impact Assessment made it clear that the Commission can play a role in this area via the establishment of a more coherent regulatory framework, but emphasised that, “as sole customers of defence equipment, it is for Member States to reform the demand side of the market” 34 (i.e. via harmonisation of requirements and consolidation of demand).

Finally, the specific objective of the Directive, as defined in the Impact Assessment, implied “a properly functioning regulatory framework at the EU level for the award of contracts in the field of defence and security. This means that EU procurement law must effectively implement the principles of the Treaty for the Internal Market in the field of defence and security and, at the same time, ensure Member States security interests.” 35 .

2.2.3.The operational objective and the main features of the Directive

The operational objective of the Directive is to limit the use of the exemptions, in particular under Article 346 TFEU, to exceptional cases, in accordance with the case law of the EU Court of Justice. The majority of contracts in the field of defence and security, including those for the procurement of arms, munitions and war material, should thus be awarded on the basis of the rules of the Directive in order to foster the application of the principles of the Treaty. At the same time, Member States' security interests must be respected 36 .

The Directive seeks to achieve this operational objective by coordinating the different national rules and laying down provisions tailor-made to the specificities of the defence and security sectors. Key elements of the Directive addressing such specificities include:

-

–Defence-specific exclusions: the Directive contains exclusions that have been adapted or newly created in order to accommodate the specific situation of the defence and security sectors. These are the exclusions on international rules, disclosure of information, intelligence activities, cooperative programmes, contract awards in third countries, and government to government sales. Some of the exclusions laid down in the Directive can relate to defence cooperation in procurement.

-

–Flexible procedures: use of the negotiated procedure with publication of a contract notice is authorised without the need for specific justification in order to allow the flexibility required to award sensitive defence and security contracts;

-

–Security of Supply: the particular importance of this issue for defence and security procurement and the specific needs of the Member States justify specific provisions. The Directive allows contracting authorities to address Security of Supply needs through criteria for the selection of suitable candidates and tenderers, contract performance conditions, and award criteria;

-

–Security of Information: protection of classified information is crucial for the award and execution of many defence and sensitive security contracts. The Directive addresses Security of Information in several provisions: as requirement for the tendering and contracting phase (Article 7), as cause for exclusion (Article 13), as contract performance condition (Articles 20 and 22), and as selection criterion (Articles 39 and 42).

-

–Review: in order to ensure compliance with transparency and competition obligations, the Directive establishes a specific review system. This system is largely based on the rules applicable to civil procurement 37 , but contains some provisions adapted to the domains of defence and sensitive security.

-

–Subcontracting: in contrast with the civil procurement Directives that provide only very limited obligations with regard to subcontracting, the (defence procurement) Directive contains a detailed set of provisions laid down in Articles 21 and Title III (Articles 50-54). These provisions, in particular, allow contracting authorities to require that successful tenderers subcontract a certain share of the main contract and/or put proposed subcontracts out to competition. At the same time, these provisions, set basic rules for the fair and transparent awarding of such subcontracts. This approach is built on the assumption that competitive subcontracting would give to sub-suppliers, and especially SMEs, a fair chance of gaining access to the supply chains of big system integrators located in other Member States.

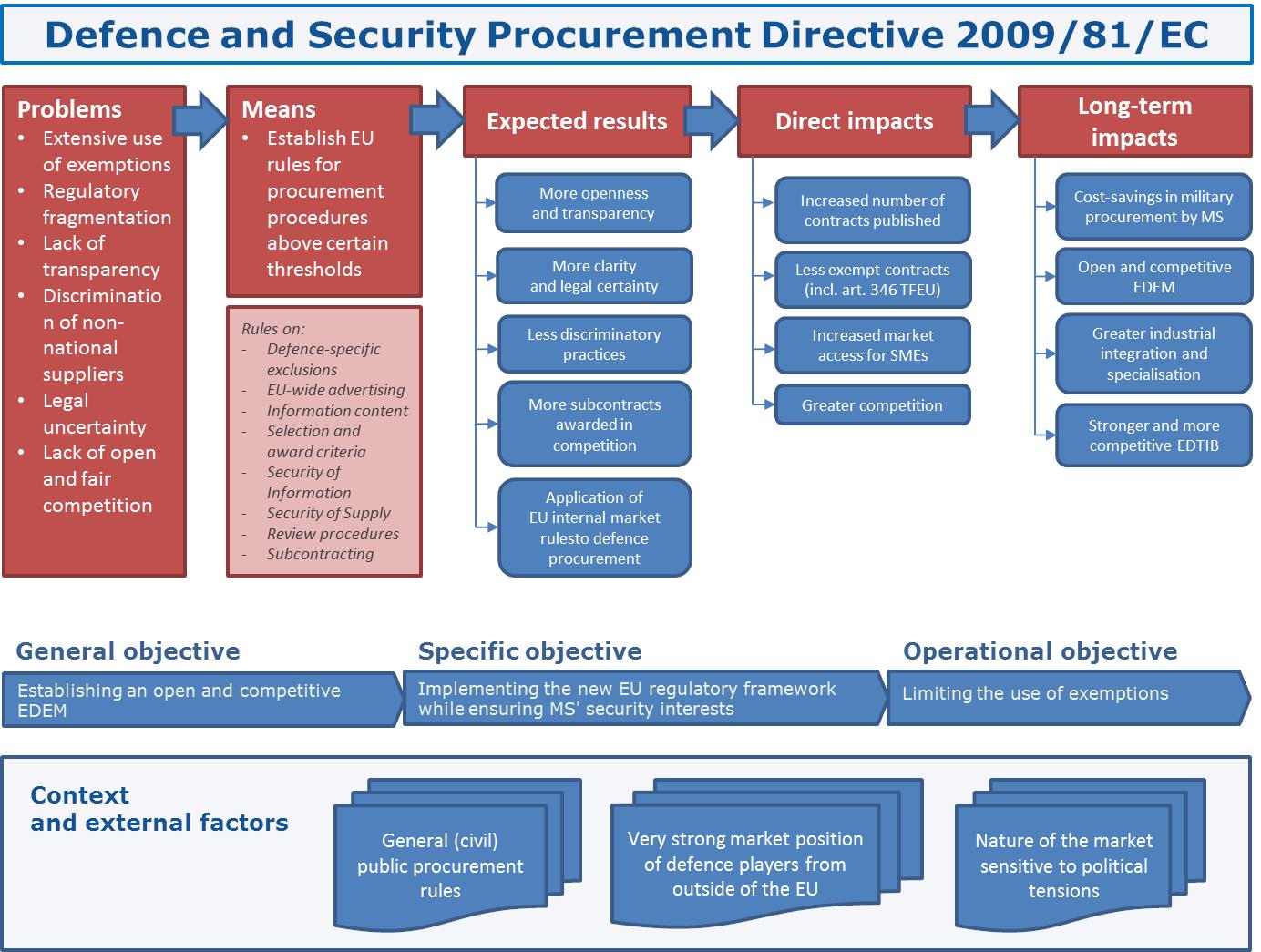

To summarise, the Directive aims at addressing the problems identified (extensive application of exemptions and non-application of competitive procurement procedures) through a set of rules specifically adapted for the defence and security sectors. The increased application of competitive procurement procedures based on transparency and equal treatment is expected to lead to more openness and transparency in defence procurement, as well as more clarity and legal certainty. This should bring about cost-savings for public authorities and a more open and efficient market and, in turn, be a contributing factor towards a stronger and more competitive industrial base in Europe. The intervention logic is presented in Figure 3 overleaf.

Figure 3: Intervention logic

2.3.Baseline: the situation before Directive 2009/81/EC

This description of the situation before the Directive is based on the analysis contained in the Impact Assessment and a study “Openness of Member State’s defence markets” by Europe Economics of November 2012 (the Baseline Study). The baseline situation was also reported in the Staff Working Document accompanying the 2013 Communication “Towards a more competitive and efficient defence and security sector” 38 .

2.3.1.Regulatory patchwork

As explained above in Section 2.2., before transposition of the Directive, exemptions were used extensively and EU public procurement rules (Directives 2004/18/EC and 2004/17/EC) were rarely applied in practice in the defence and security sector. Most procurement contracts were awarded on the basis of different national rules 39 . Each Member State followed different rules as regards publication, technical specifications, and procedures.

With particular regard to publication, the extent to which contract notices were published (either at the EU or national level) differed widely. The frequency of publication and accessibility of contract notices also varied greatly across Member States 40 .

2.3.2.EU-wide publication of business opportunities

The Impact Assessment found that, in the reference period 2000-2004, the publication in the field of defence was relatively rare, even with regards to non-military and non-sensitive procurement such as uniforms or certain services. The publication levels appeared to be even lower, if not marginal, for military procurement; in these cases, publication seemed to concern mainly procurement of “simple”, low value equipment, as well as non-sensitive works and services 41 .

According to the Baseline Study, more than 1 500 notices for defence contracts 42 of a value of roughly 4 billion EUR were published on Tenders Electronic Daily (OJ/TED) 43 from 2008 to 2010 included. On top of that, nearly 300 notices for contracts of roughly 4.76 billion EUR were published on the Electronic Bulletin Board (EBB) of the EDA 44 .

Table 3: Contracts advertised on OJ/TED and EBB in 2008-2010 [number of contracts, value in million EUR]

Publication source |

Number |

Value |

||||||

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

Total |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

Total |

|

TED |

415 |

447 |

686 |

1 548 |

513 |

2 626 |

885 |

4 024 |

EBB |

126 |

90 |

80 |

296 |

2 518 |

1 348 |

900 |

4 766 |

Total |

541 |

537 |

766 |

1 844 |

3 031 |

3 974 |

1 785 |

8 790 |

Source: The Baseline Study, p. 30

Hence, in the period 2008-2010, 1 844 defence contract notices were published EU-wide. The total value of these contracts was estimated to be nearly 8.8 billion EUR 45 , which was equivalent to 3.3% 46 of the EU’s total defence procurement expenditure in the same period (263.23 billion 47 EUR, 2008-2010). In the context of comparisons with the baseline which will be made later in this evaluation, it shall be noted that the Baseline Study referred to defence procurement expenditure as reported by the EDA, while in this report, the main source of data used to determine defence procurement expenditure is Eurostat COFOG database 48 (see: Section 2.1.1.). If the baseline OJ/TED and EBB data were compared with the 2008-2010 COFOG defence procurement expenditure, the share would increase to 3.6%. Nonetheless, if the filtering OJ/TED of notices would be more conservative (as the one applied in this report, see: Section 5.3) the percentage would probably decrease, potentially to a figure close to the baseline estimate of 3.3%. For the above explained reasons, the share of 3.3%, despite its caveats, has been maintained as the reference figure for the baseline period.

2.3.3.Cross-border awards

According to the Baseline Study, cross-border contracts published in OJ/TED and EBB in 2008-2010 amounted to 2.26 billion EUR 49 . Consequently, the share of cross-border awards published through the above channels in the reference years equalled 0.86% 50 of the total defence procurement expenditure.

-

3.Evaluation questions

The following table contains a list of questions that will be addressed in the course of this evaluation, to guide the analysis of the performance of the Directive. The questions are grouped under the five evaluation criteria that will look into the effectiveness, efficiency, relevance, coherence and EU added value of the Directive.

Table 4: Evaluation questions

Main evaluation questions |

Evaluation questions detailed |

|

Effectiveness |

To what extent have the objectives of the Directive been achieved? To what extent the observed changes can be attributed to the Directive? What are the factors, if any, affecting the implementation of the Directive? |

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

Efficiency |

To what extent has the intervention been cost effective? |

|

Relevance |

To what extent is the intervention still relevant? |

|

|

||

Coherence |

To what extent is this intervention coherent with other interventions which have similar objectives? |

|

|

||

EU added value |

To what extent do the issues addressed continue to require action at EU level? |

|

-

4.Method

The analysis presented in this document was based on several data sources, in particular: notices published in OJ/TED, data published by EDA and NATO, IHS Jane’s Defence & Security Intelligence database and Eurostat, as well as consultations with Member States and stakeholders (including a public on-line survey). The findings of this evaluation are compared with the situation before the entry into the force of the Directive, as analysed in the Baseline Study.

As mentioned in the introduction, the evaluation covers years 2011-2015. Given the short time that has elapsed since the entry into force of the provisions, it can be expected that the conclusions about the Directive’s impact on the EDEM and, especially, the EDTIB would be very difficult to reach. Therefore the present evaluation assesses whether we are on track to meeting the objectives it sets and the expectations made at the time of its adoption. The problem of insufficient time lag of this evaluation has been already pointed out in the Baseline Study: “A comparison in 2016 of, say, 2013-2015 with 2008-2010 might not capture much of the Directive’s impacts: 2013 is only one year later than the end of the transposition phase. Comparisons in 2017 of 2014-2016 (or possibly 2015-2016) with 2008-2010 would offer a better chance of capturing impacts.” 51 Similarly, it has been also pointed out in the Impact Assessment that ”Given the life cycle of defence equipment (and their related services, especially maintenance), an evaluation of the economic impact should be contemplated in the long term (no sooner than 10 years).” 52 .

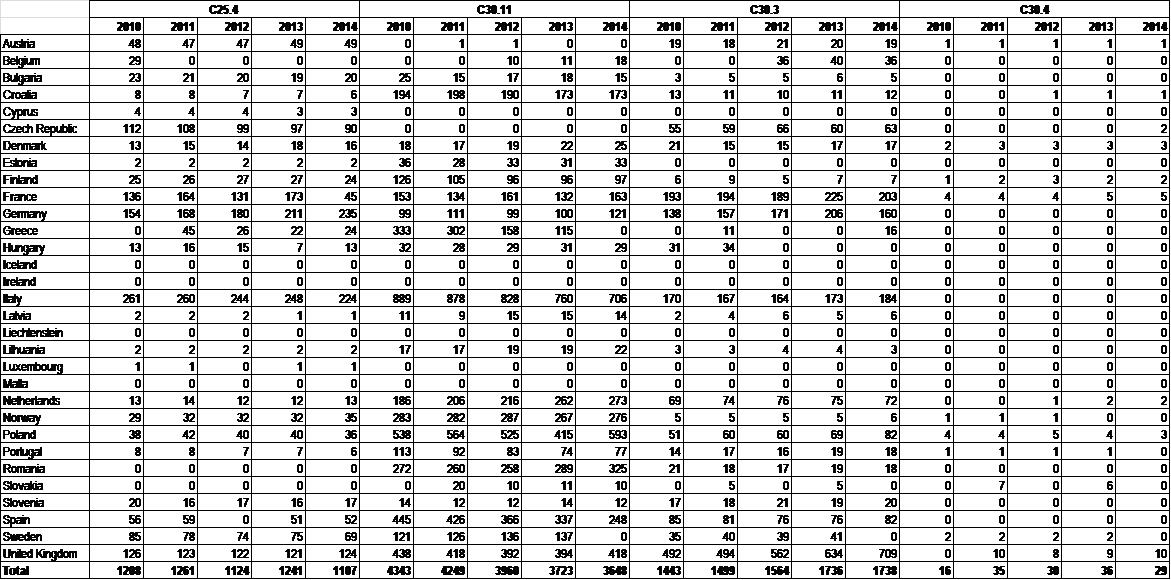

4.1.OJ/TED data

The main source of data used in this evaluation was extracted from OJ/TED, which is the online version of the Supplement to the Official Journal of the EU dedicated to European public procurement. The OJ/TED dataset contains information provided by national contracting authorities about procurement procedures they implement(ed) and includes for instance the Common Procurement Vocabulary (CPV) 53 chosen to describe the subject-matter of the contract, the price of awarded contracts, the name of the winning firm and the legal regime applied (the Directive or the civil procurement Directives).

Procurement transactions which were of particular pertinence in the context of this evaluation were those published on notices dedicated to defence and security procurement 54 . Additionally, the analysis also covered a subset of publications on voluntary ex-ante transparency notices (VEATs) when the contracting authority indicated that the publication falls under the Directive and notices published under the civil procurement Directives, if their subject matter was linked to defence or/and security. The latter was established by retaining notices which referred to CPV codes listed in Table 42 and Table 43 in Annex III.

From the analytical point of view, the most valuable information about procurement comes from the contract award notices, as they refer to procedures that have been concluded (i.e. contracts which were attributed to a particular company for an agreed price). For this reason, the following analysis is mainly based on the contract award notices.

Before launching any descriptive analysis of OJ/TED publications, the raw dataset was subject to manual scrutiny in order to verify its quality. The analysis of OJ/TED data included in this evaluation is based on the manually corrected datasets, unless specified otherwise. The scope of manual corrections is explained in detail in Annex III.

4.2.Other data sources

In addition to OJ/TED data, data from other sources were also used, in particular:

-

•Eurostat: COFOG data ( http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/government-finance-statistics/data/database ) and Structural business statistics (SBS) data ( http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/structural-business-statistics/data/database ),

-

•IHS Jane’s ( http://www.janes.com/ ), especially the following modules: Jane's Defence Procurement, Jane’s Defence Industry & Markets,

-

•The European Defence Agency (EDA) ( https://www.eda.europa.eu/ ),

-

•Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) ( https://www.sipri.org/ ),

-

•North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) ( http://www.nato.int/ ),

-

•AeroSpace and Defence Industries Association of Europe (ASD) ( http://www.asd-europe.org/home/ ).

The extent to which each of the above data was used and the limitations linked to its scope or availability, if any, are described in Annex III (Method). This Annex contains also references to other ancillary data sources used to underpin this evaluation.

4.3.Stakeholders consultations

The stakeholders consultation methods for this evaluation have been designed to reach all potential stakeholders as well as the general public, and to gather detailed technical feedback from more directly involved stakeholders and experts. In the light of this, the consultations included an internet-based public consultation (online survey) and several complementary consultation meetings with key stakeholders. More information is provided in Annex II.

4.4.Methodological issues and data availability

The current evaluation has been carried out without encountering major unexpected problems linked to methodological and/or data analysis issues. The economic research underpinning this evaluation relied heavily on descriptive statistics of the OJ/TED dataset which was available in a structured format and fit for automated processing. The raw OJ/TED was subject to manual scrutiny to ensure its adequacy and corrected for basic errors or missing information. Additionally, examination of the data, especially with regards to the contract award values, has also been performed by the representatives of two Member States who volunteered to complete the missing information for their countries. As such, the manual corrections affected less than 5% of the observations, which suggest that the original dataset was of a relatively good quality.

Some data availability issues where encountered in areas where such problems could have been expected (e.g. procurement exempt from the application of the Directive). This part of the market was analysed using data from a private provider (IHS Jane’s), which as such was not technically demanding, but rather raised questions about its coverage/completeness and potential overlaps with OJ/TED. The estimation of compliance costs under the Directive also included “business as usual” costs and costs deriving from national legislation. It was impossible to disentangle the above components of the cost estimate due to technical limitations in the raw dataset used. More information about the methodology used is provided in Annex III.

As far as the EDTIB impact is concerned, it was noted that definite conclusions are difficult to draw at this stage, as insufficient time has elapsed since the adoption of the Directive and potential impact on the industry would need more time to materialise. In parallel, there were also issues with the unavailability of recent data about the industry (e.g. beyond 2014) in Eurostat and/or ASD. Additionally, the main Eurostat database which is typically used to describe patterns across chosen industries – the Structural business statistics (SBS) - is not well adapted to the defence sector, as it partially covers non-defence activities (e.g. civil aerospace and shipbuilding). This problem is known and has been mentioned in several previous publications about the defence sector, including the Baseline Study: “The ‘defence industry’ is not an industry in a statistical sense. There is no classification ‘defence equipment’ in the EU’s Nomenclature générale des Activités économiques dans les Communautés Européennes (NACE).” 55 .

Notwithstanding those limitations, the evaluation is based on a review of best available quantitative and qualitative evidence of causality between actions and effected changes. It made extensive use of stakeholders' and experts' view on the functioning of the different provisions of the Directive.

-

5.Implementation state of play

This section includes an overview of the process that led Member States to convert the Directive into their national legal orders with some significant delays for some Member States, a summary of the results of the technical analysis of the transposition measures adopted by Member States process, a brief description of developments concerning the related issue of offsets regulations, some background information on the Commission departments’ activities to ensure compliance with the Directive, and, finally, a quantitative analysis of the uptake of the Directive.

5.1.Transposition

5.1.1.The transposition process (August 2011-May 2013)

Under Article 72 of the Directive, Member States had to “adopt and publish the laws, regulations and administrative provisions necessary to comply with the Directive” (i.e. transpose it in their national legal orders) by 21 August 2011. Only 3 Member States had notified complete transposition of the Directive to the Commission by 21 August 2011, and a fourth Member State notified complete transposition in September 2011.

The Commission therefore opened infringement procedures against 23 Member States (Article 258 TFEU) by sending letters of formal notice. As a result, by March 2012, 15 additional Member States had notified complete transposition. For the remaining 8 Member States (Austria, Bulgaria, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, the United Kingdom, and Slovenia) the Commission continued the infringement procedures for non-communication of transposition measures and issued reasoned opinions 56 . By September 2012, Austria, Bulgaria, Germany and the United Kingdom notified complete transposition and the Commission closed the infringement procedures relating to them.

In September 2012, the Commission decided to refer Poland, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Slovenia to the Court of Justice since these Member States had not notified the complete transposition of the Directive 57 . By April 2013, these four Member States did so and the Commission closed the infringements procedures. The Commission did not consider the transposition measures notified by Portugal to be complete and issued a reasoned opinion in March 2013 58 . Following the reply of the Portuguese authorities and notification of further transposition measures in April 2013, this infringement procedure was also closed.

It is, therefore, only from May 2013 that the provisions of the Directive have been fully transposed in the national legal orders of all Member States.

5.1.2.Technical analysis of transposition measures

The Commission departments have analysed Member States’ transposition measures to verify their conformity with the provisions of the Directive. The Commission departments have not identified fundamental problems in terms of conformity of national transposition measures, i.e. problems that would jeopardise the overall functioning of the Directive. However, this analysis has shown that, in several Member States, there are certain issues to be clarified on the transposition in national legislation of some specific provisions of the Directive.

This Section of the SWD is based on a preliminary analysis conducted in the context of the evaluation of the Directive. It is without prejudice to the Commission’ position concerning possible breaches of Union law.

5.1.2.1.Scope, thresholds and exclusions

The correct transposition of the provisions defining the scope of the Directive (Articles 1 and 2), and the exclusions (Article 12 and 13) is an essential pre-requisite for the uptake of the Directive, and compliance with the principles of competition, transparency and equal treatment. These provisions have been broadly transposed in a correct manner. One Member State seems to have transposed Article 2(c) broadening the scope with regard to the award of contracts for non-military security. Similarly, another Member State seems to have broadened the scope of Article 2(a) by referring to military “and law enforcement purposes”.

Article 9(5) third subparagraph provides that the application of the Directive to each lot may be waived if the lots are below a certain value. In one Member State, a small change in the wording of the corresponding national provision could allow contracting authorities/entities to waive such application in cases different than those provided for in the Directive.

Two Member States have transposed Article 12(c) without including the words “purchasing for its purposes”. One Member State seems to have broadened the scope of Article 13(b) by referring to the purposes of the bodies pertaining to the intelligence system rather than to intelligence activities.

5.1.2.2.Negotiated procedure without publication

Since it allows contracting authorities to derogate from the fundamental requirements on transparency and EU-wide competition, the correct transposition of Article 28 on the use of the negotiated procedure without publication of a contract notice is also essential. Only very few and particular issues have been identified with the transposition of this provision. In one Member State, the time limit of five years in Article 28(3)(a) does not refer to “recurrent contract”. Another Member State did not transpose the provision in Article 28(4)(b) obliging contracting authorities/entities to disclose the possible use of the procedure as soon as the first project is put up for tender. Four Member States seem not to have transposed the second part of the same provision laying down an obligation to take into account the cost of subsequent works or services to calculate the estimated value of the contract for the purposes of the thresholds under Article 8.

5.1.2.3.Exclusion grounds (Article 39)

Four Member States did not transpose Article 39(1) fourth subparagraph or at least the reference that clarifies that contracting authorities/entities’ requests of evidence about the personal situation of a candidate or tenderer have to relate, where needed, to natural persons such as company directors. One Member State seems to have extended the scope of mandatory exclusion grounds of Article 39(1) to economic operators submitting multiple offers and to those involved in the preparation of procurement documents. Two Member States broadened the possibility for contracting authorities/entities to waive mandatory exclusion grounds provided for in Article 39(1) third subparagraph.

Two Member States have not transposed Article 39(2)(d) providing for the exclusion for grave professional misconduct, and another Member State has not transposed Article 39(2)(e) on the exclusion of economic operators which lack the reliability to exclude security risks. Two Member States have not transposed Article 39(2)(h) on the exclusion of economic operators who are guilty of serious misrepresentation in supplying the information on their personal situation or who have not supplied such information; in one Member State, the corresponding national provision narrows the scope of this exclusion ground.

5.1.2.4.Time limits (Articles 33 and 34)

Two Member States transposed Article 33(3) by referring directly to the time limit of 22 days, instead of making it clear that the normal time limit is 36 days and 22 days is the absolute minimum that cannot be in any way shortened further.

Article 34(4) provides time limits for the contracting authorities/entities to send to economic operators additional information on the contracts documents. Five Member States have either not transposed this provision, or slightly reduced through different mechanisms the time available to economic operators.

5.1.2.5.Other issues related to the rules on contracts

According to Article 5(2), groups of economic operators may submit tenders or put themselves forward as candidates. In one Member State, the corresponding national provision allows contracting authorities/entities to exclude groups of undertakings if based on objective reasons.

Article 18(3)(a) second subparagraph provides that contracting authorities/entities, when drafting the technical specifications, have to accompany every reference to standards with the expression “or equivalent”. One Member State seems to have converted this provision into national law without including this wording.

Article 22, third subparagraph provides that Member States have to recognise the security clearances which they consider equivalent to those issued in accordance with their national law. This means that, where there are bilateral security agreements or arrangements concerning the equivalence of security classifications and security requirements, contracting authorities/entities have to recognise security clearances granted by the national security authority of the other Member State party to this agreement or arrangement 59 . In two Member States national legislation do not explicitly provide for this obligation to recognise security clearances in the above-mentioned circumstances.

In two Member States, the national provisions corresponding to Article 29(3) allow contracting authorities/entities to conclude framework agreements with a single economic operator without defining all the terms for the award of specific contracts based on the agreement.

Article 32(1) provides for the minimum content to be included in the notices for publication at EU level; one Member State has not transposed this provision in its national legislation. In addition, Article 32(5) prohibits contracting authorities/entities to publish notices at national level before the date on which they are sent to the Commission for publication at EU level. It also provides that notices published at national level cannot include information other than that contained in the notices sent for publication at EU level. In two Member States, the relevant national provisions do not contain the explicit prohibitions lay down in Article 32(5).

Article 37(1) lays down an obligation on contracting authorities/entities to draw up a written report on the selection procedure, and provides for mandatory elements to be included in the report. In two Member States, the national provisions do not mention all these elements.

Article 38 regulates various aspects of the conduct of procedures. Two Member States appear not to have expressly transposed Article 38(1), which sets out the sequencing of procedures from the application of exclusion grounds to the qualitative selection and the award of the contract. In two Member States, the provisions transposing Article 38(3) third subparagraph do not lay down the obligation, in case of re-publication of contract notice, to invite the candidates selected upon the first publication.

Article 38(5) regulates the situation where the contracting authorities/entities exercise the option of reducing the number of solutions or of tenders. In three Member States, this provision has not been transposed.

One Member State appears not to have transposed in national legislation Article 49(1) and Article 49(2) on abnormally low tenders. According to these provisions, where tenders appear to be abnormally low, contracting authorities/entities have to request in writing details of the constituent elements of the tender and to verify these elements by consulting the tenderer.

5.1.2.6. Subcontracting

Article 21(1) lays down i.a. a prohibition to require successful tenderers to discriminate against potential subcontractors on grounds of nationality. Two Member States seem not to have explicitly transposed this provision. One Member State appears not to have transposed any of the provisions on subcontracting (Articles 21 and 50 to 53).

5.1.2.7. Rules to be applied to reviews

According to Article 56(3), Member States are obliged to ensure that contracting authorities/entities cannot conclude the contract before the review body’s decision. One Member State seems not to have transposed this provision, and another has introduced changes that make the prohibition less stringent.

Article 57(2), fourth subparagraph, imposes an obligation on contracting authorities/entities to include in the communication of the award decision a summary of the relevant reasons and a precise statement of the exact standstill period applicable. Two Member States have not transposed this provision in national legislation, and one has not included the reference to the statement of the applicable standstill period.

Article 58 allows Member States to provide for specific derogations from the standstill period. One of these derogations concerns contracts based on a framework agreement. However, according to Article 58(c), Member State which decide to use this option have to ensure, in two specific cases, that such contracts based on a framework agreement are ineffective. Four Member States seem to have used the option, but not explicitly transposed these provisions on ineffectiveness. In one Member State, the national provision provides for ineffectiveness only in one of the two cases.

Article 60(1) imposes on Member States the obligation to provide for ineffectiveness of contracts in specific cases. It seems that two Member States have not transposed this provision, while three Member States appear not to have included in the relevant national provisions all the cases for ineffectiveness. Article 60(3) provides that Member States may enable review bodies not to declare contracts ineffective when this is required by overriding reasons relating to a general interest; the same provision clarifies that economic interests directly related to the contract do not constitute such overriding reasons. In one Member State, the national provision transposing Article 60(3) admits such economic reasons to be overriding reasons. In addition, six Member States have not transposed either Article 60(4) or Article 60(5), which provide for mandatory non-application of ineffectiveness in given cases.

5.1.3.Offsets / industrial return regulations in the context of transposition

This section addresses the issue of offsets regulations, which is highly relevant in the context of the process of transposition of the Directive. The practice of concrete offsets or industrial return requirements in specific public procurement procedures is covered below in Section 6.1.1.4.

Offsets are compensations that many governments in the world require when they procure defence equipment from non-national suppliers. This is often to ensure an economic/industrial return on defence investment. Offsets can take various forms: they can be directly related to the subject-matter of the contract, indirect but limited to the military sphere, or indirect non-military.

Whatever their form, offsets requirements are, from an EU law standpoint, restrictive measures which go against the basic principles of the Treaty, because they discriminate against economic operators, goods and services from other Member States and impede the free movement of goods and services. They can only be justified on the basis of one of the Treaty-based derogations, in particular Article 346 TFEU. However, these derogations must be limited to exceptional and clearly defined cases, and the measures taken must not go beyond the limits of such cases. They have to be interpreted strictly, and the burden of proof that the derogation is justified lies with the Member State which invokes it 60 .

The Impact Assessment highlighted the negative and discriminatory effects of offsets upon procurement procedures. It noted that offsets “give a considerable advantage to big prime contractors, which normally have better means than smaller competitors to arrange offsets deals”; “if military offsets are required, prime contractors have to sub-contract to companies located in the buying country. Consequently, they cannot use the most competitive sub-contractors to organise their supply chain, but must give preference to sub-suppliers of a certain nationality”; “if non-military offsets are required, the same effect spills over into civil markets: non-military contracts are awarded on the basis of nationality than competitiveness” 61 .

The Impact Assessment assessed a number of options with regard to offsets, and concluded that not mentioning them in the proposal for the Directive was the best-suited one 62 . In fact, since offsets requirements violate basis rules and principles of primary EU law, a secondary law instrument like the Directive cannot allow, tolerate, or regulate them. The Impact Assessment added that the issue of compatibility of offsets with EC law had to be addressed in the light of the Treaty and the Commission’s Interpretative Communication 63 .

Before the adoption of the Directive, 18 Member States maintained offsets regulations requiring compensation from non-national suppliers when they procured defence equipment abroad 64 . These regulations obliged contracting authorities to systematically (i.e. for all contracts or for all contracts above a certain value) require offsets when purchasing defence equipment from foreign suppliers abroad. They were clearly incompatible with EU primary law as well as the correct transposition and application of the Directive.

Consistently with the option selected with the Impact Assessment, the Commission departments therefore engaged, since 2010, with Member States to make sure that these offsets regulations were abolished or revised in the context of the process of transposition of the Directive. Member States have indeed either abolished or revised their offsets regulations. The content of revised offsets regulations varies significantly across Member States, but they have one key feature in common. Under the revised regulations, offsets are no longer required systematically (i.e. for all contracts or for all contracts above a certain value) in connection with defence purchases from abroad based on grounds of clear economic nature. The revised rules provide that offsets can only be required, following a case-by-case analysis, where the conditions of Article 346 TFEU are met.

The revised offsets regulations of those Member States that have chosen to maintain them in place do not seem per se incompatible with EU law. The question remains, however, of whether - and to what extent - the concrete application of these revised rules in procurement practice in individual cases is compliant with EU law, and in particular with the strict conditions for the use of Article 346 TFEU.

5.2.Compliance activities concerning individual procurement cases

Section 5.1. above describes the Commission activities concerning the transposition of the Directive, and the related issue of offsets/industrial return regulations. This paragraph seeks to explain the Commission departments’ work so far about compliance of Member States’ concrete individual procurements with the rules of the Directive.

It should be pointed out that, in the period 2011-2015 (and also until September 2016), the Commission departments have received only 1 complaint from an economic operator involved in a specific defence procurement procedure, and no complaint from economic operators involved in procedures for the procurement of high-value, complex military equipment. As it emerged in the stakeholders' consultations with regard to access to review procedures, defence companies only usually have one customer in each country, and therefore try not to antagonise them. This may also help explain the absence of complaints to the Commission. It should be pointed out, however, that the absence of complaints from competitors, which have the potential of providing comprehensive and well-substantiated information, severely affects the compliance activities of Commission departments, due to the difficulties of gathering ex officio such information about concrete defence procurement procedures. Other relevant factors in this context are the relative novelty of the rules, and the sensitivity of the sector.

In the period 2011-2015, the Commission departments contacted Member States authorities to seek clarifications on 11 individual procurements. In 2016, further contacts concerning other 17 individual procurements have been undertaken. The main focus of these exchanges has been clarifications about the legal grounds for the non-application of the Directive and, in some cases, for the use of offsets/industrial return requirements.

5.3.Uptake of the Directive

As explained in Section 2.3., before the entry into force of the Directive, the publication of defence and security procurement was relatively limited and took place mainly through OJ/TED publications under the civil procurement Directives and on the EBB run by the EDA. According to the Baseline Study, in the period 2008-2010, 1 844 defence contract notices were published EU-wide for the estimated total value of around 8.8 billion EUR. The following sections discuss how the situation has changed in the EU since the adoption of a legal instrument dedicated to defence and security procurement.

5.3.1.Defence and security procurement under the Directive

Since the entry into force of the Directive, more than 8 700 notices have been published in OJ/TED under the standard forms dedicated to defence and security procurement 65 . As explained in Section 4 and Annex III, following a manual scrutiny of the raw OJ/TED data, around 250 notices have been removed from the original dataset, mainly because their subject matter was judged as not being related to defence and security procurement. Additionally, contract award notices from Belgium and the Netherlands have also been manually corrected by the representatives of the respective Member States. All analysis of OJ/TED data included in this document is based on the manually corrected dataset. The retained dataset related to publications under the Directive contained 8 526 notices ( Table 5 ).

Table 5: Notices published under the Directive, by year and type [number of notices]

Year |

Prior information notice |

Contract notice |

Contract award notice |

Subcontract notice |

Total |

2011 |

2 |

95 |

16 |

0 |

113 |

2012 |

85 |

739 |

348 |

2 |

1 174 |

2013 |

100 |

896 |

820 |

16 |

1 832 |

2014 |

160 |

1 226 |

1 165 |

5 |

2 556 |

2015 |

166 |

1 343 |

1 333 |

9 |

2 851 |

Total |

513 |

4 299 |

3 682 |

32 |

8 526 |

Source: OJ/TED, manual corrections by DG GROW

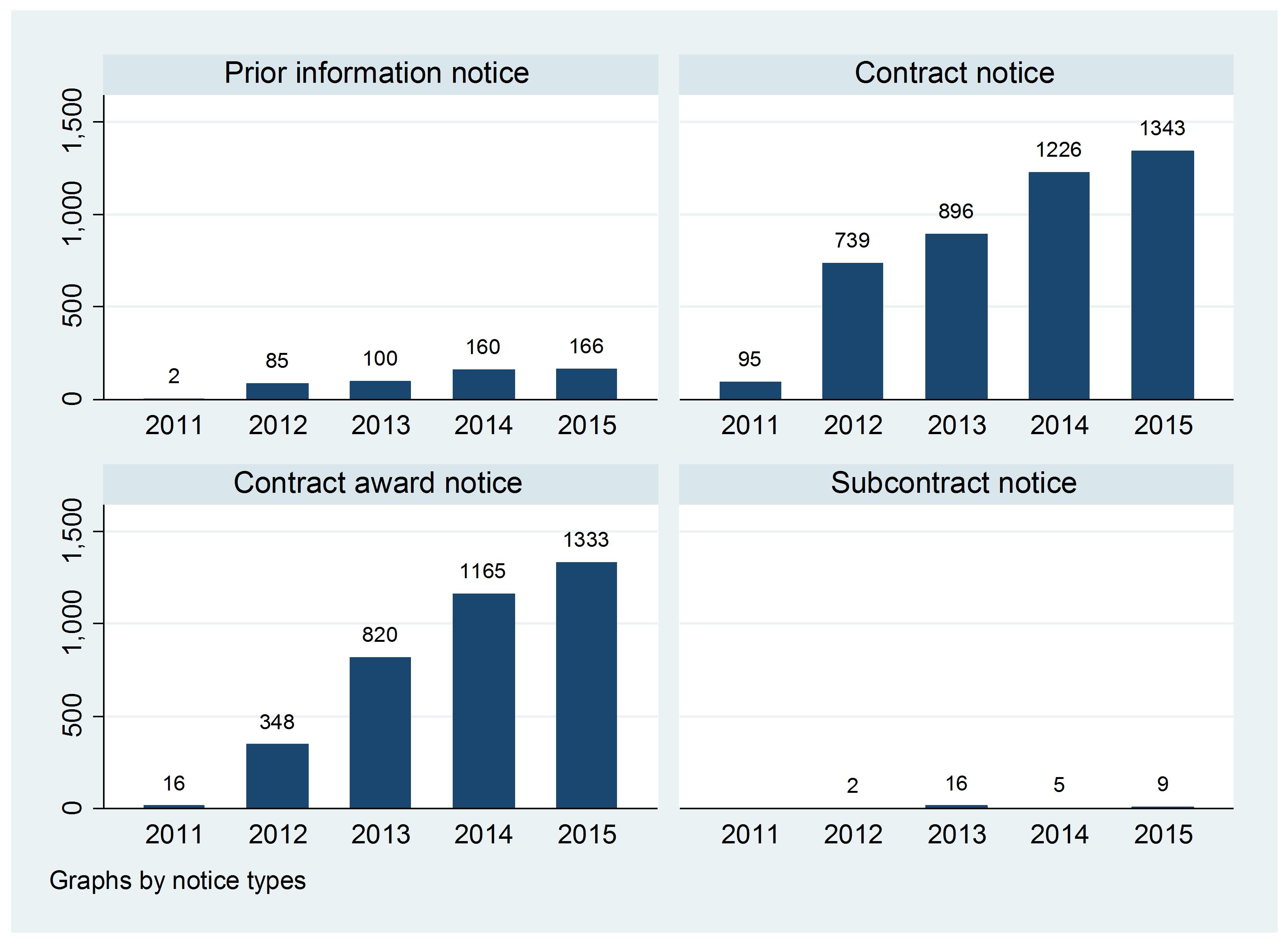

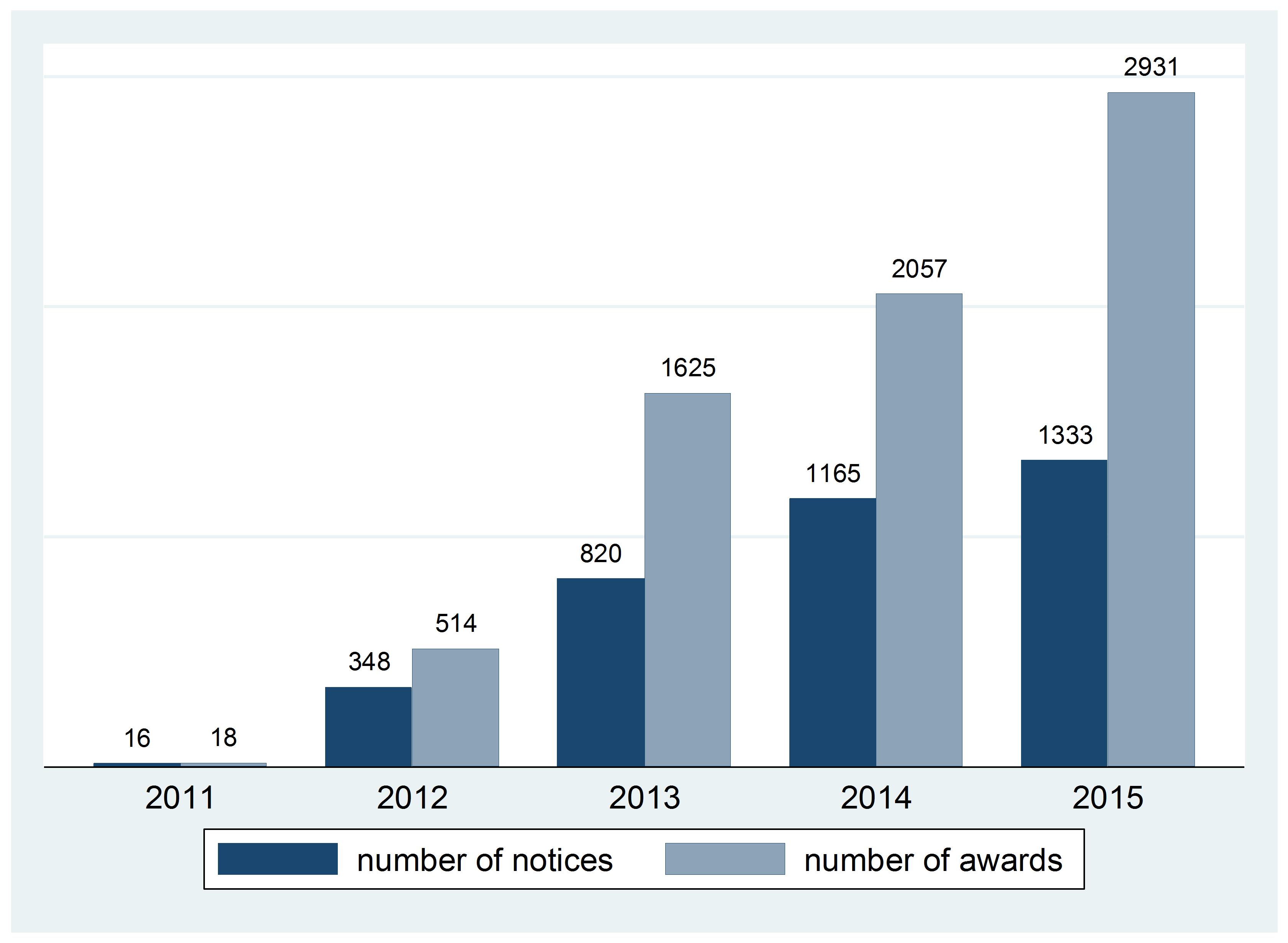

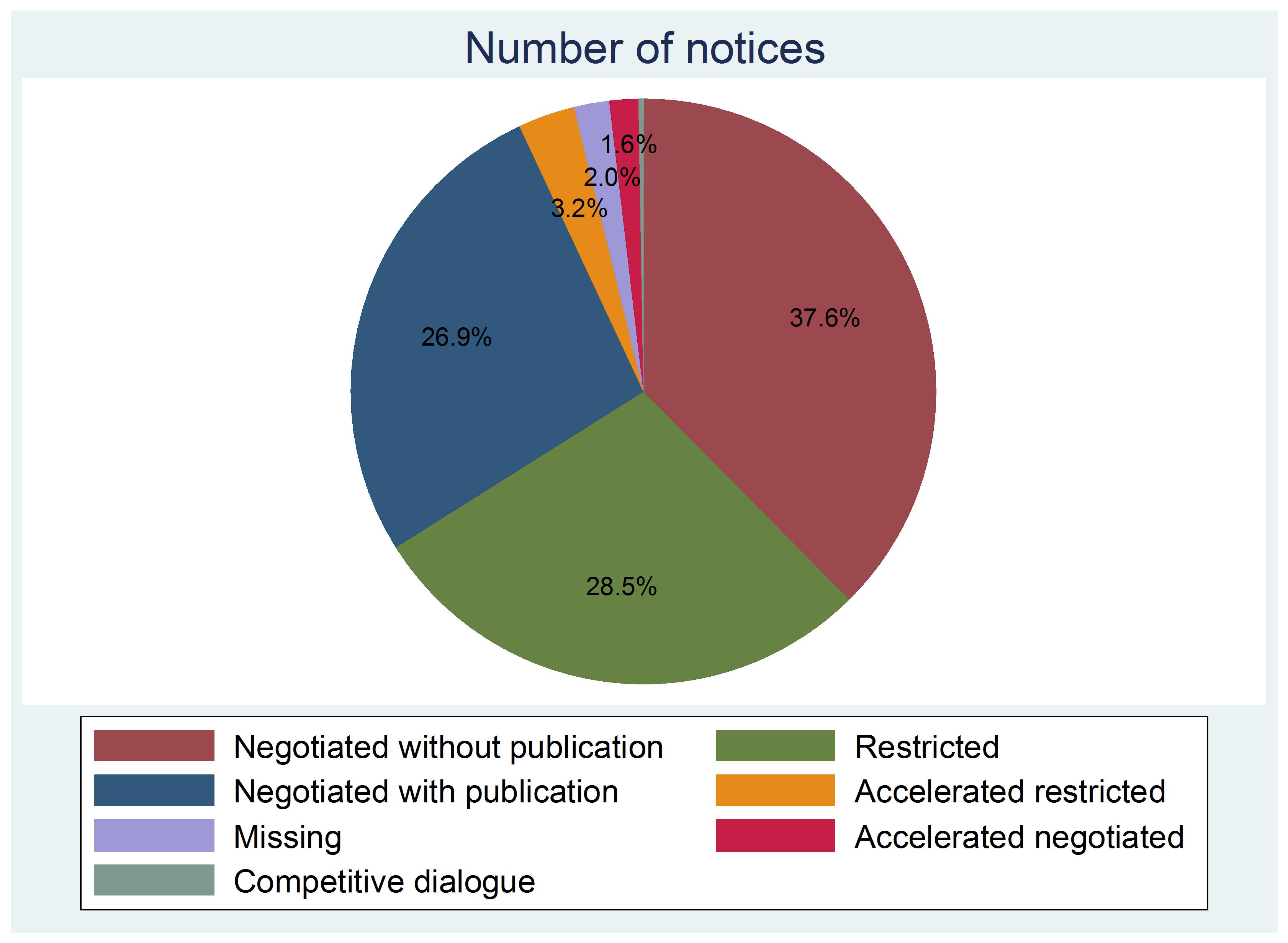

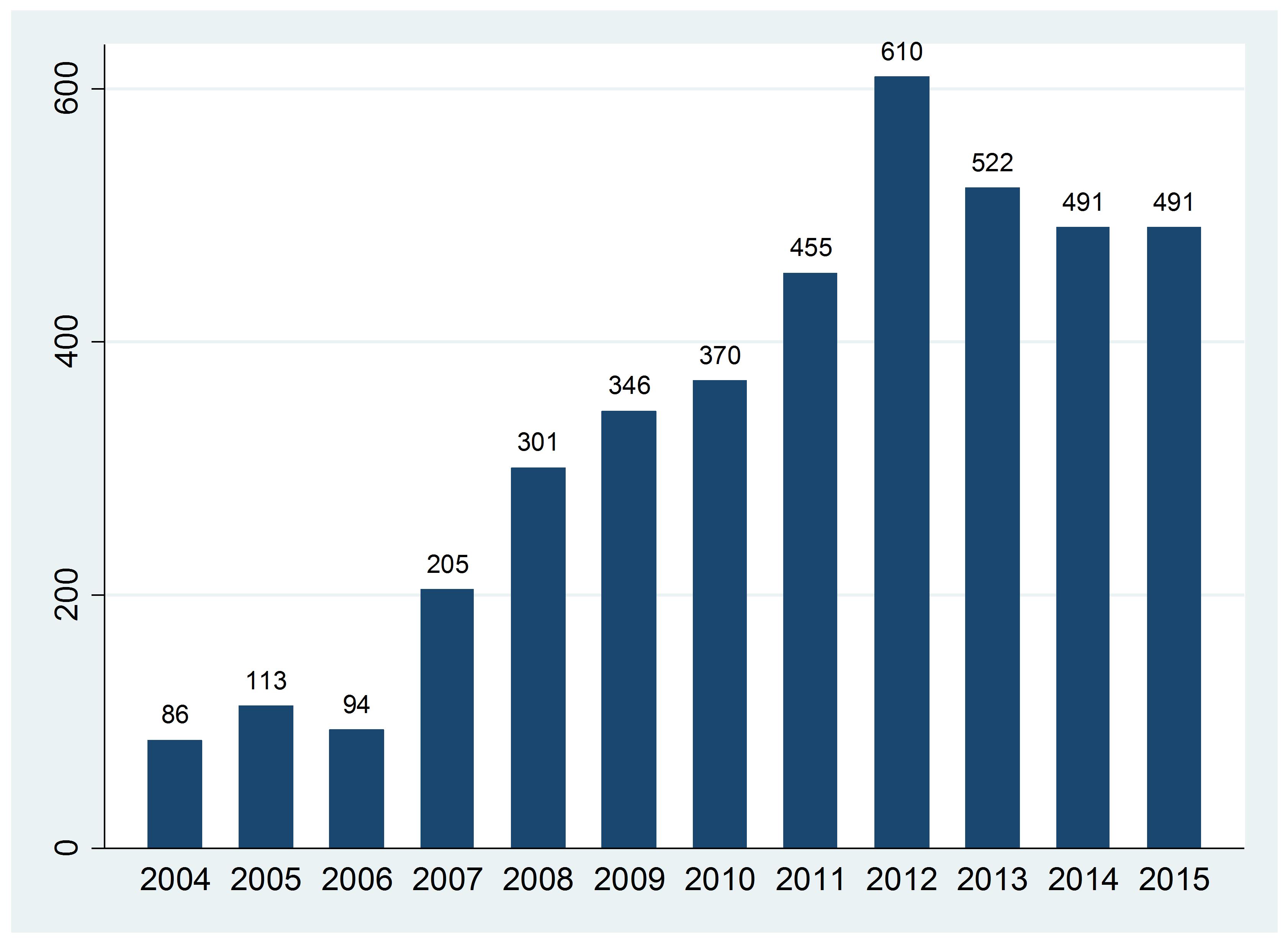

Upon entry into force, the uptake of the Directive was almost immediate and has shown a clear upward trend. As presented in Figure 4 , the use of procurement notices available under the Directive has been increasing each year, with the exception of the subcontract notices 66 which clearly stagnated at barely a few publications per year.

Figure 4: Notices published under the Directive, by year and type [number of notices]

Source: OJ/TED, manual corrections by DG GROW

A total of 3 682 contract award notices has been published in OJ/TED over the analysed period of time, containing 7 145 distinct contract awards 67 . The difference stems from the fact that a single contract award notice may refer to the award of one or many contracts (contract awards). Out of the total number of contract awards notices published in 2011-2015, 3 121 contained just one contract. The remaining 15% of notices featured many awards – the largest number in the sample was a notice containing 365 separate awards.

Figure 5: Contract award notices and awards published under the Directive, by year [number of notices and awards]

Source: OJ/TED, manual corrections by DG GROW

The number of awards (awarded contracts) published under the Directive was in a steady increase over the last five years, rising from only 18 in 2011 to 2 931 awards in 2015 ( Figure 5 ). The total number of awarded contracts equalled, after manual corrections, 7 145 in 2011-2015.

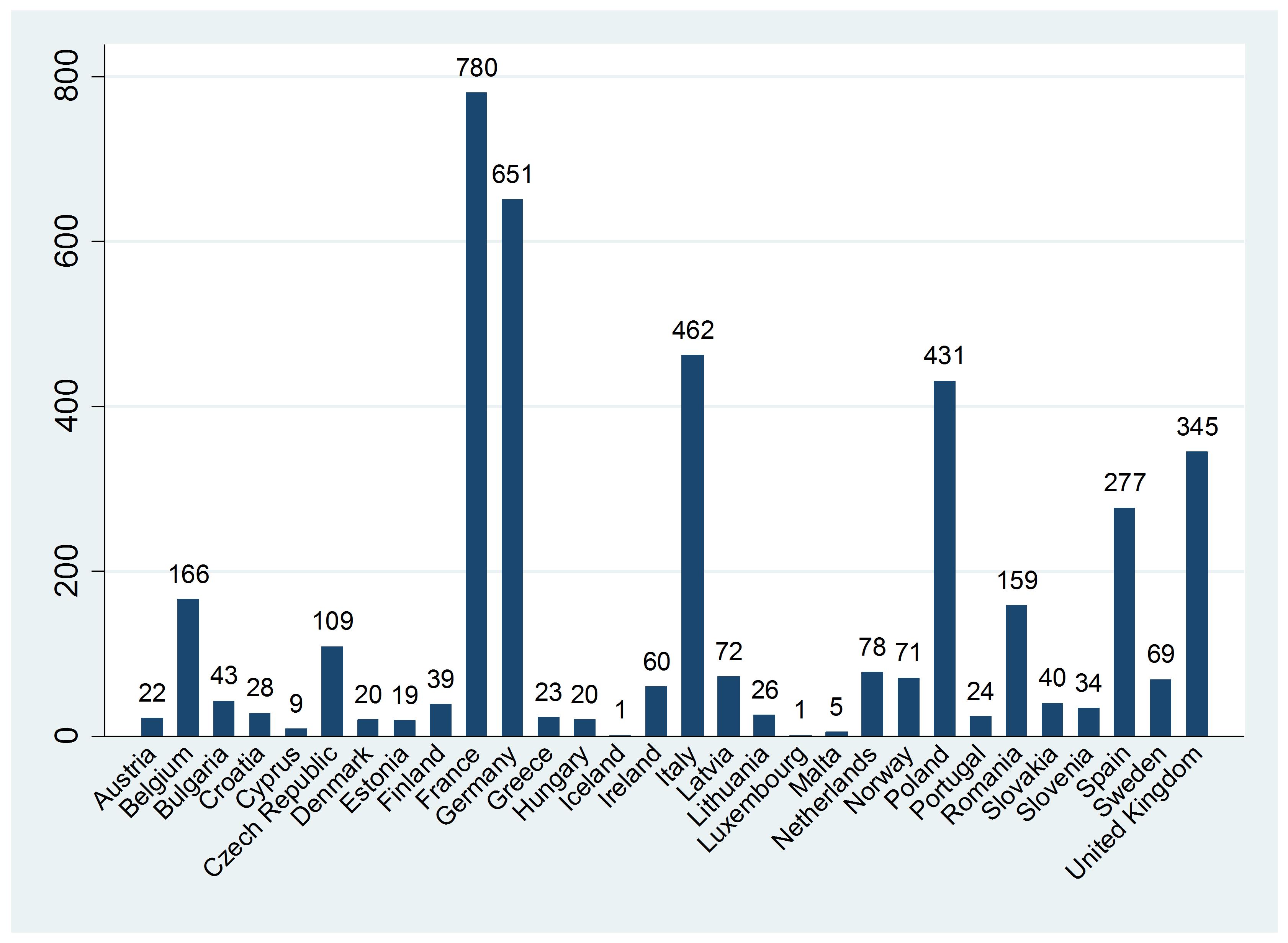

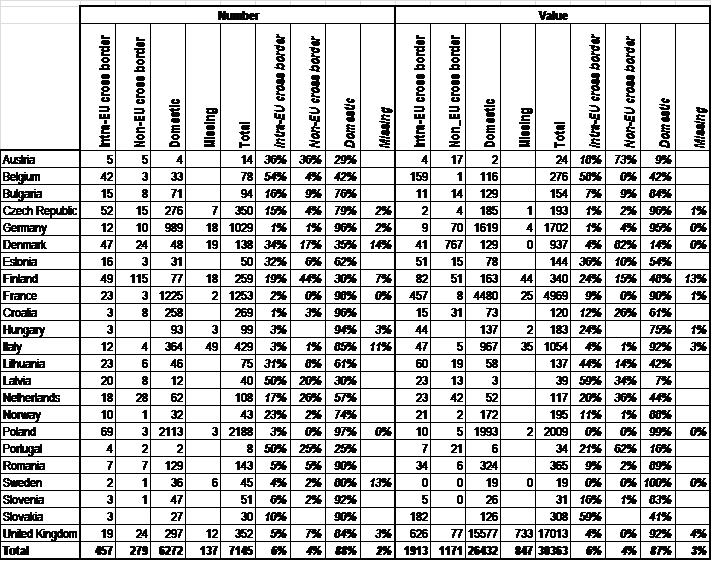

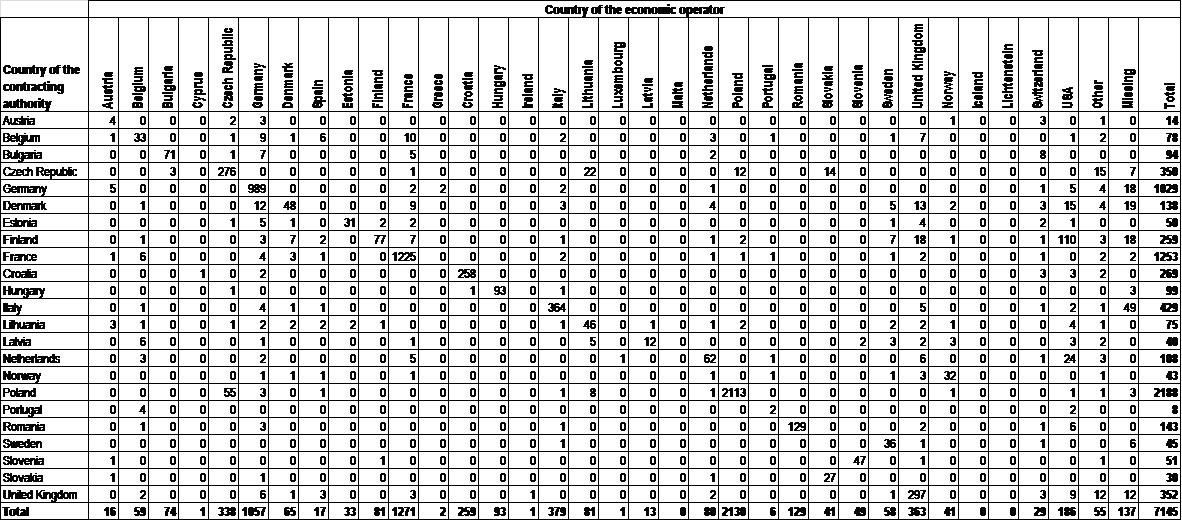

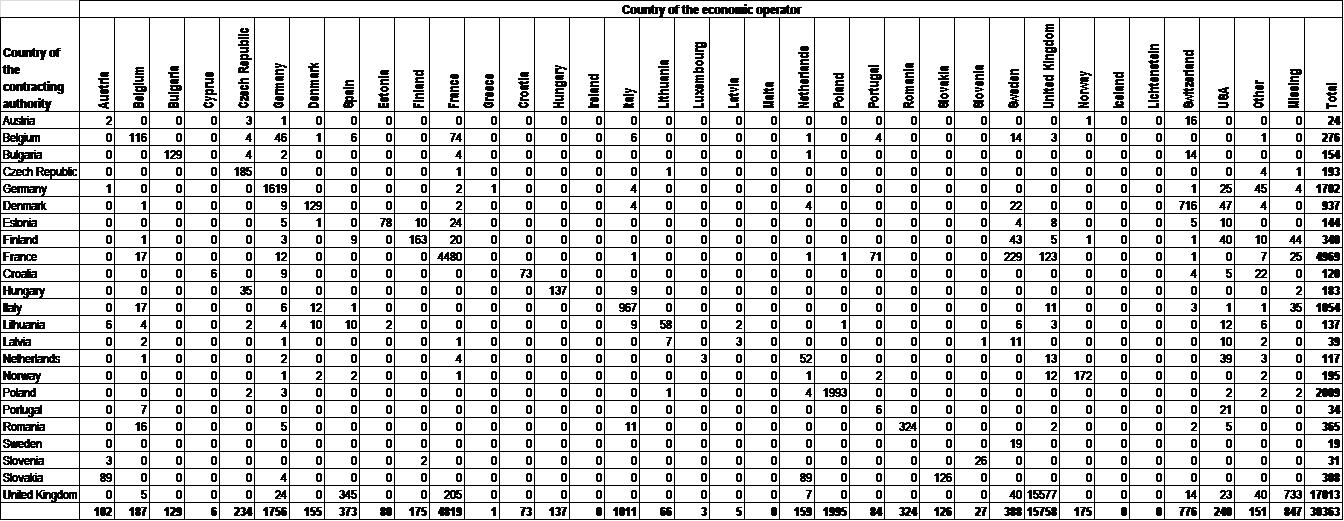

5.3.1.1. Use of the Directive by countries

The total value of 3 682 contract award notices published under the Directive accounted for nearly 30.85 billion EUR over the five years which are covered by the current analysis (2011-2015). However, the extent to which Members States implemented the Directive remained uneven. In terms of the number of notices published, more than 70% of the publications concerning awarded contracts were made by authorities from five Member States: Germany, France, Italy, Poland and the United Kingdom ( Table 6 ).

Table 6: Contract award notices published under the Directive, by country and year [number of notices]

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

Total |

|

Austria |

1 |

4 |

1 |

5 |

11 |

|

Belgium |

3 |

28 |

25 |

14 |

70 |

|

Bulgaria |

2 |

2 |

17 |

19 |

35 |

75 |

Croatia |

16 |

31 |

47 |

|||

Czech Republic |

9 |

16 |

37 |

75 |

137 |

|

Denmark |

17 |

23 |

32 |

40 |

112 |

|

Estonia |

7 |

14 |

19 |

40 |

||

Finland |

26 |

36 |

45 |

39 |

146 |

|

France |

39 |

230 |

225 |

246 |

740 |

|

Germany |

3 |

87 |

202 |

251 |

271 |

814 |

Hungary |

1 |

11 |

18 |

7 |

10 |

47 |

Italy |

10 |

106 |

97 |

105 |

88 |

406 |

Latvia |

5 |

4 |

12 |

21 |

||

Lithuania |

3 |

8 |

18 |

25 |

54 |

|

Netherlands |

4 |

5 |

23 |

31 |

63 |

|

Norway |

3 |

26 |

29 |

|||

Poland |

3 |

32 |

171 |

185 |

391 |

|

Portugal |

8 |

8 |

||||

Romania |

21 |

58 |

48 |

127 |

||

Slovakia |

5 |

1 |

5 |

15 |

26 |

|

Slovenia |

8 |

7 |

10 |

25 |

||

Sweden |

2 |

9 |

13 |

10 |

34 |

|

United Kingdom |

30 |

53 |

86 |

90 |

259 |

|

Total |

16 |

348 |

820 |

1 165 |

1 333 |

3 682 |

Source: OJ/TED, manual corrections by DG GROW

Between 2011 and 2015 there were no publications of contract award notices by contracting authorities from six countries: Cyprus, Greece, Ireland, Malta, Luxembourg and Spain 68 . It shall be noted however that these countries have published a number of contract award notices with a defence-related subject-matter under the civil procurement Directives. Spain for example, kept on publishing under the civil regime even after transposition of the Directive.

In terms of the contract value, an overview of publications by Member States also shows significant differences across the EU, as presented in Table 7 . More than a half of the value of published contracts has been awarded by authorities from the United Kingdom (nearly 17 billion EUR over the analysed five years, albeit this result was heavily influenced by one contract award notice valued at around 6 billion GBP 69 ). France, Poland, Germany and Italy followed in the ranking (with publications estimated at approximately 5 to 1 billion EUR).

Table 7: Contract award notices published under the Directive, by country and year [value in million EUR]

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

Total |

|

Austria |

0.62 |

3.79 |

2.03 |

17.23 |

23.68 |

|

Belgium |

4.34 |

145.58 |

106.20 |

19.83 |

275.95 |

|

Bulgaria |

0.58 |

0.70 |

90.14 |

15.60 |

46.51 |

153.54 |

Croatia |

43.71 |

75.82 |

119.53 |

|||

Czech Republic |

20.03 |

23.25 |

55.15 |

94.33 |

192.75 |

|

Denmark |

34.02 |

42.74 |

15.95 |

844.69 |

937.39 |

|

Estonia |

16.15 |

23.79 |

104.34 |

144.28 |

||

Finland |

25.48 |

84.82 |

143.35 |

91.45 |

345.10 |

|

France |

45.64 |

817.71 |

2 000.91 |

2 105.16 |

4 969.42 |

|

Germany |

2.15 |

280.92 |

344.99 |

409.46 |

664.58 |

1 702.11 |

Hungary |

0.57 |

52.40 |

23.23 |

57.96 |

49.06 |

183.23 |

Italy |

18.73 |

144.68 |

389.79 |

395.11 |

116.55 |

1 064.86 |

Latvia |

4.38 |

8.84 |

25.72 |

38.94 |

||

Lithuania |

1.41 |

37.26 |

22.85 |

75.52 |

137.04 |

|

Netherlands |

2.27 |

6.73 |

26.58 |

81.25 |

116.84 |

|

Norway |

3.69 |

191.47 |

195.16 |

|||

Poland |

4.37 |

123.30 |

700.20 |

1 181.23 |

2 009.11 |

|

Portugal |

34.04 |

34.04 |

||||

Romania |

11.50 |

216.64 |

136.56 |

364.70 |

||

Slovakia |

6.39 |

1.75 |

286.26 |

13.67 |

308.07 |

|

Slovenia |

17.00 |

4.95 |

9.17 |

31.13 |

||

Sweden |

1.15 |

0.18 |

0.18 |

17.68 |

19.19 |

|

United Kingdom |

820.29 |

592.59 |

2 811.81 |

13 259.46 |

17 484.14 |

|

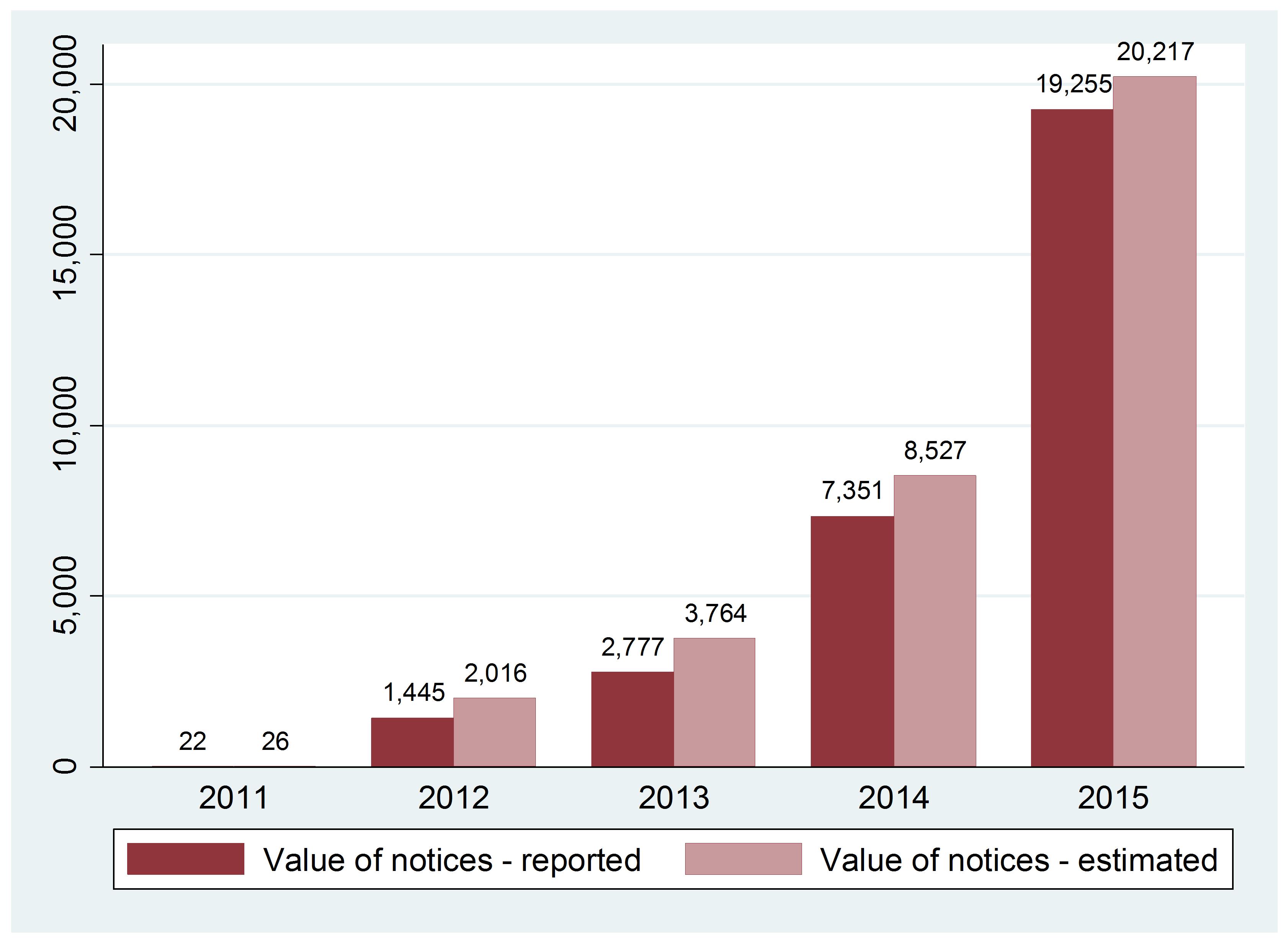

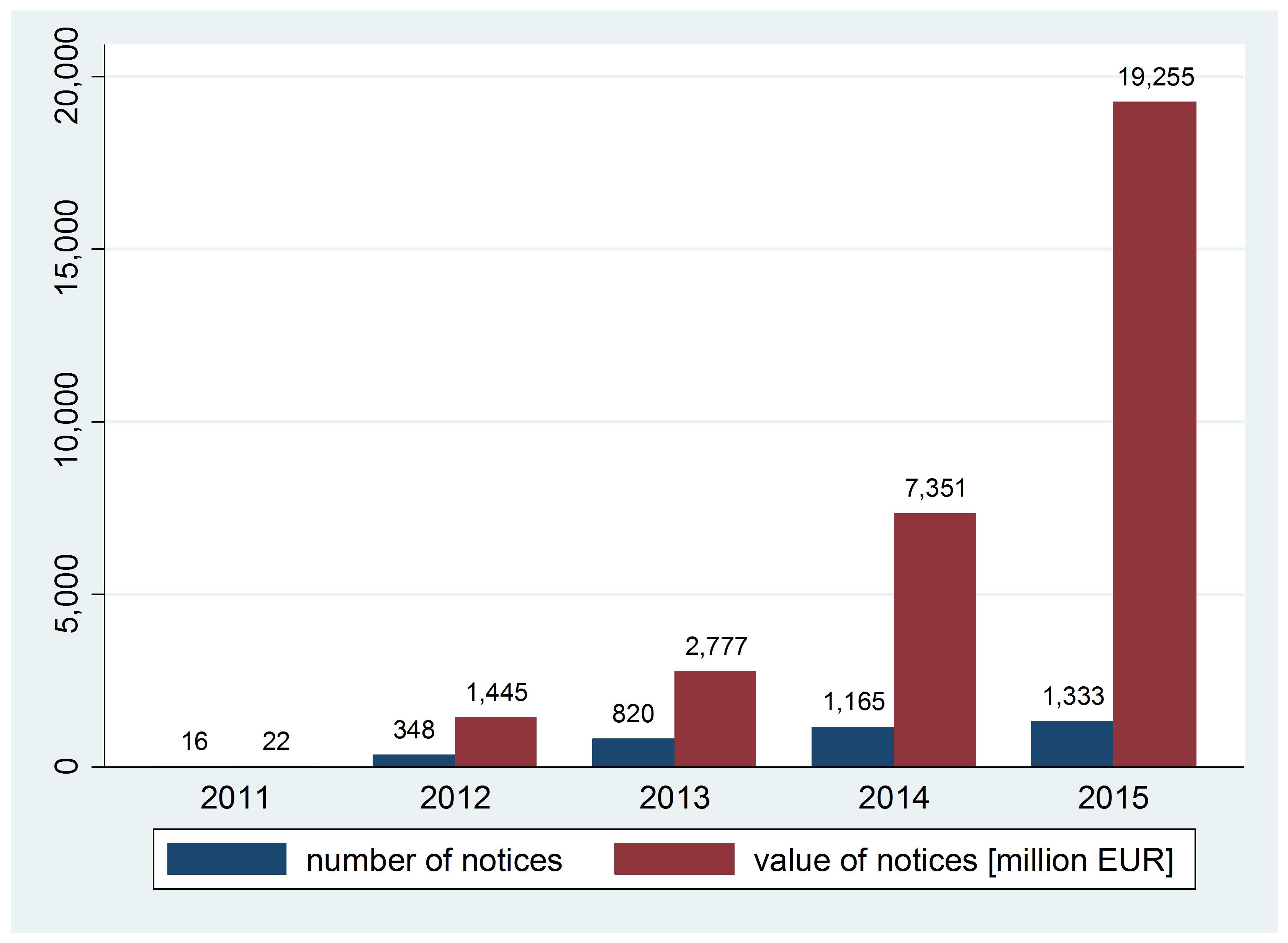

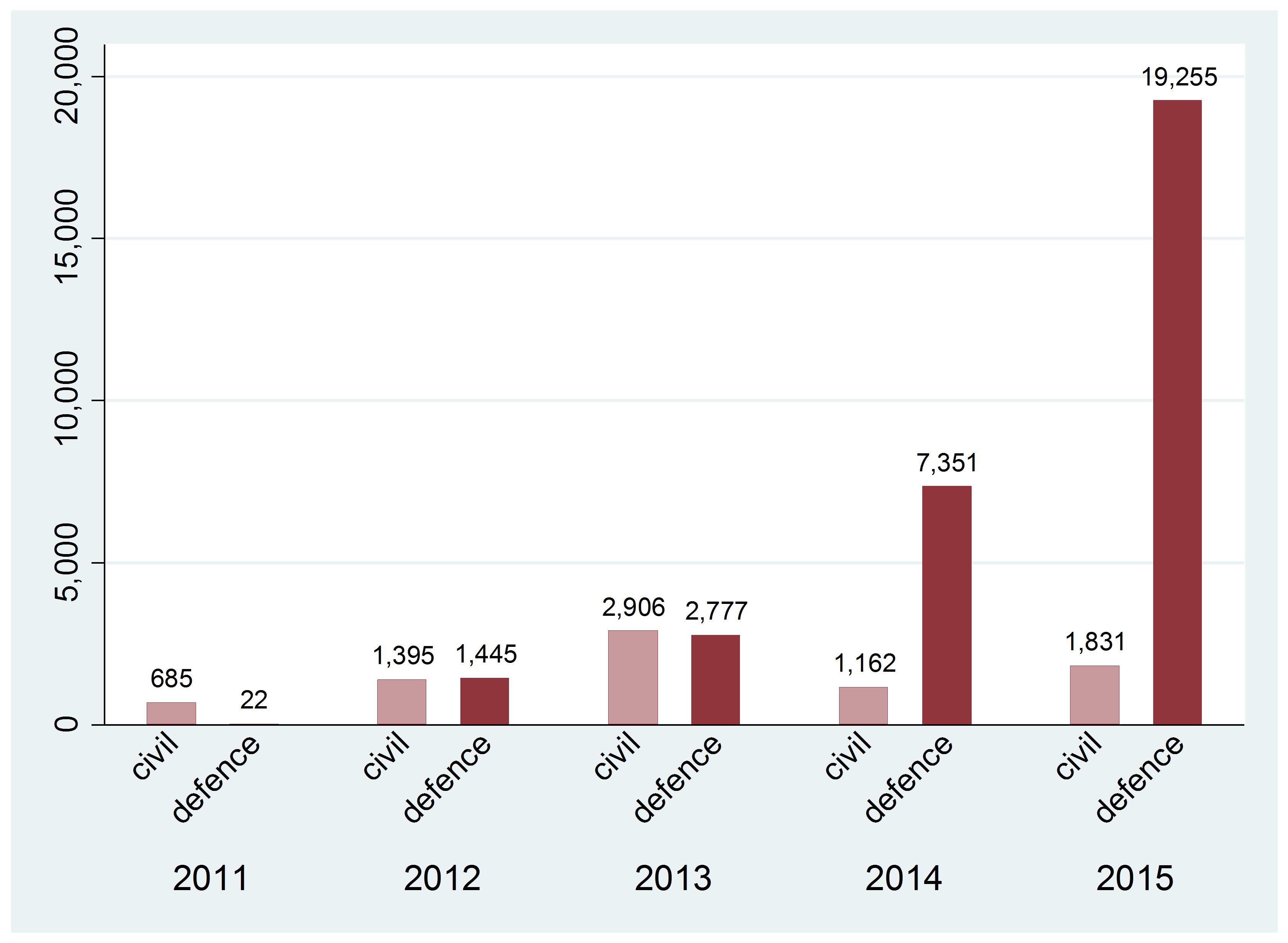

Total |

22.03 |

1 444.72 |

2 776.88 |

7 351.24 |

19 255.31 |

30 850.19 |

Source: OJ/TED, manual corrections by DG GROW

The contracting authorities from the United Kingdom not only published the largest contract under the Directive, but also as much as 20 out of 44 contract award notices featuring the total value exceeding 100 million EUR (Table 8).

Table 8: Contract award notices with values above 100 million EUR published under the Directive in 2011-2015, by country [number of notices]

Country |

Freq. |

Percent |

Cum. |

United Kingdom |

20 |

45.45 |

45.45 |

France |

14 |

31.82 |

77.27 |

Germany |

3 |

6.82 |

84.09 |

Denmark |

2 |

4.55 |

88.64 |

Italy |

2 |

4.55 |

93.18 |

Poland |

2 |

4.55 |

97.73 |

Slovakia |

1 |

2.27 |

100 |

Total |

44 |

100.00 |

Source: OJ/TED, manual corrections by DG GROW

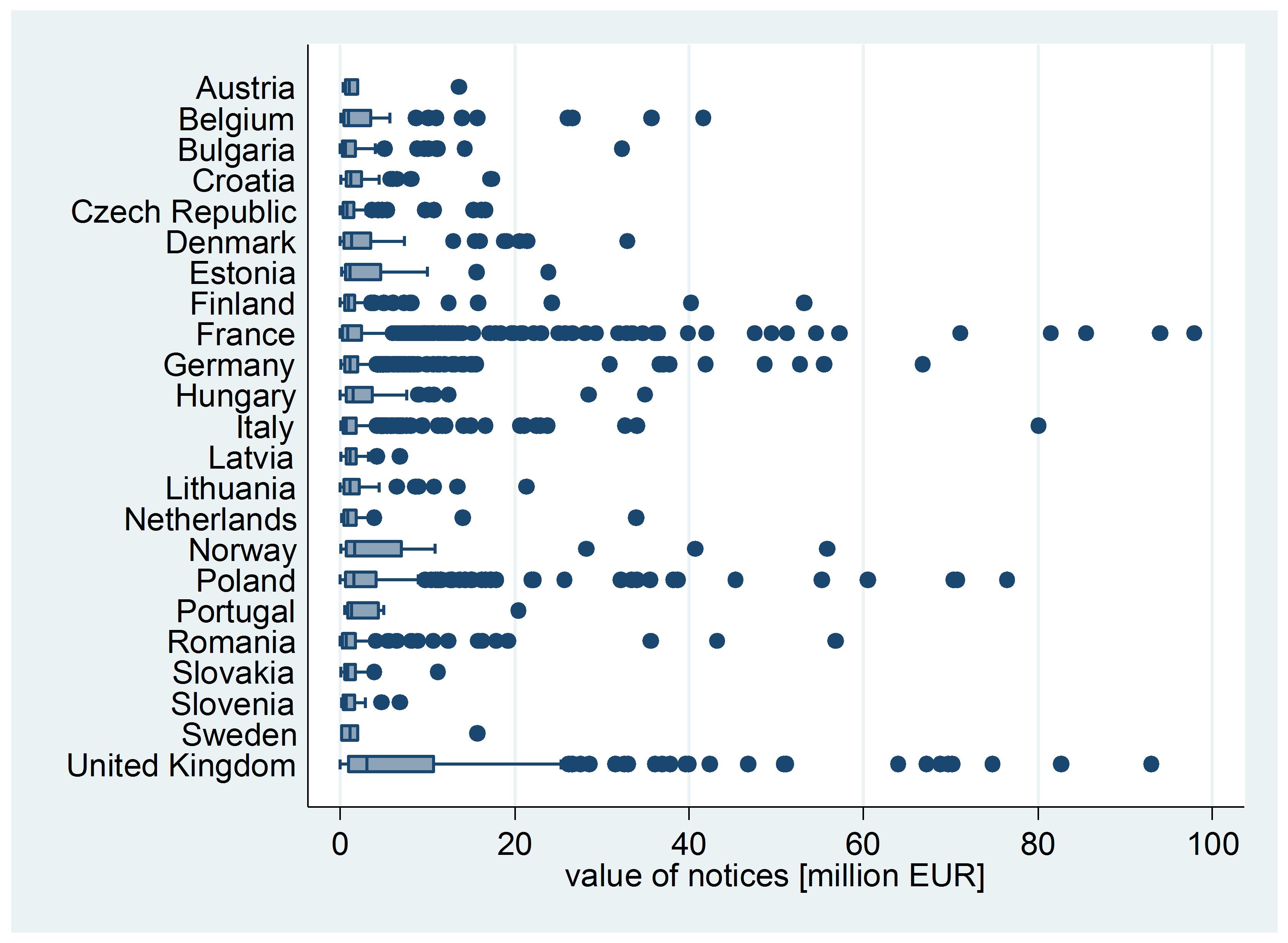

The differences between countries were also significant for contracts below 100 million EUR. The box and whisker plots for each country presented in Figure 6 illustrate the median, quartiles, the range of data and its outliers.

Figure 6: Distribution of contract award notices with values below 100 million EUR published under the Directive in 2011-2015, by country [value in million EUR]

Source: OJ/TED, manual corrections by DG GROW

As seen on the graph, most observations are concentrated around the low value contracts with the right tail of the distribution being considerably longer. The majority of high value observations / outliers (marked by dots) were noted for the United Kingdom and France.

When analysing the awarded contracts in more detail, it appears that high value contracts carried out under the Directive were rather few. The reported contracts frequently concerned various auxiliary defence activities e.g. repair and maintenance services, building management services, logistic services, etc.

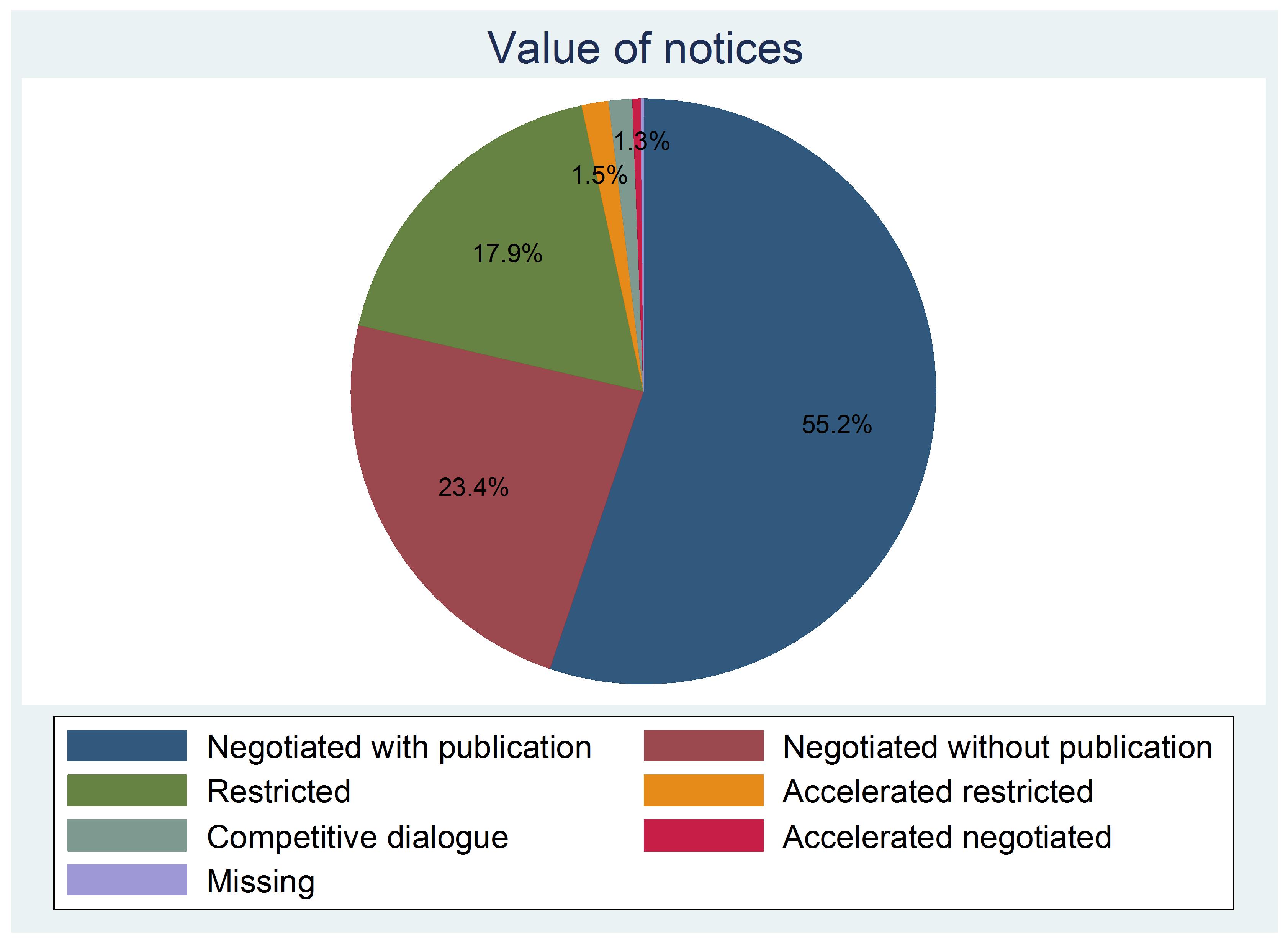

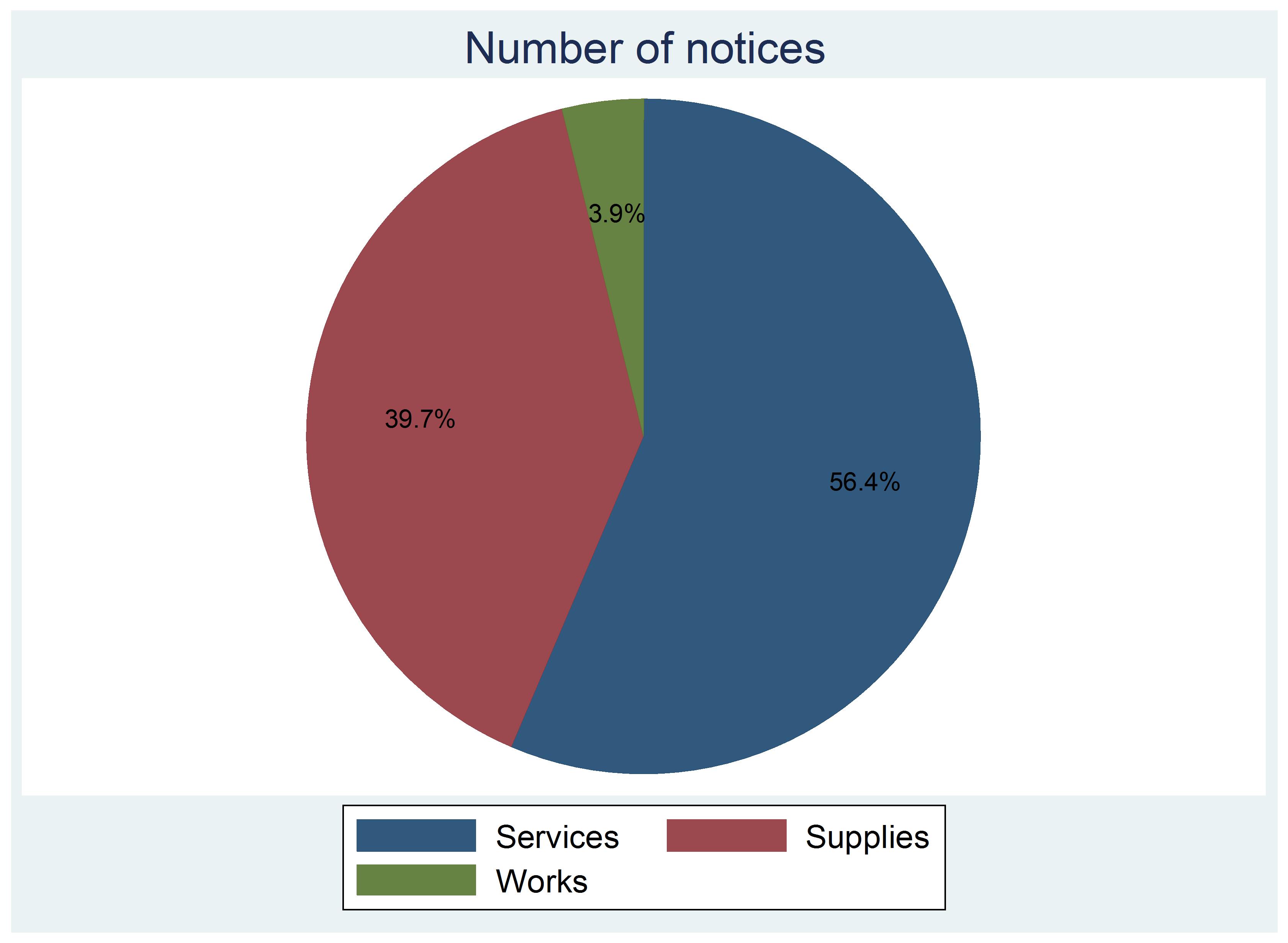

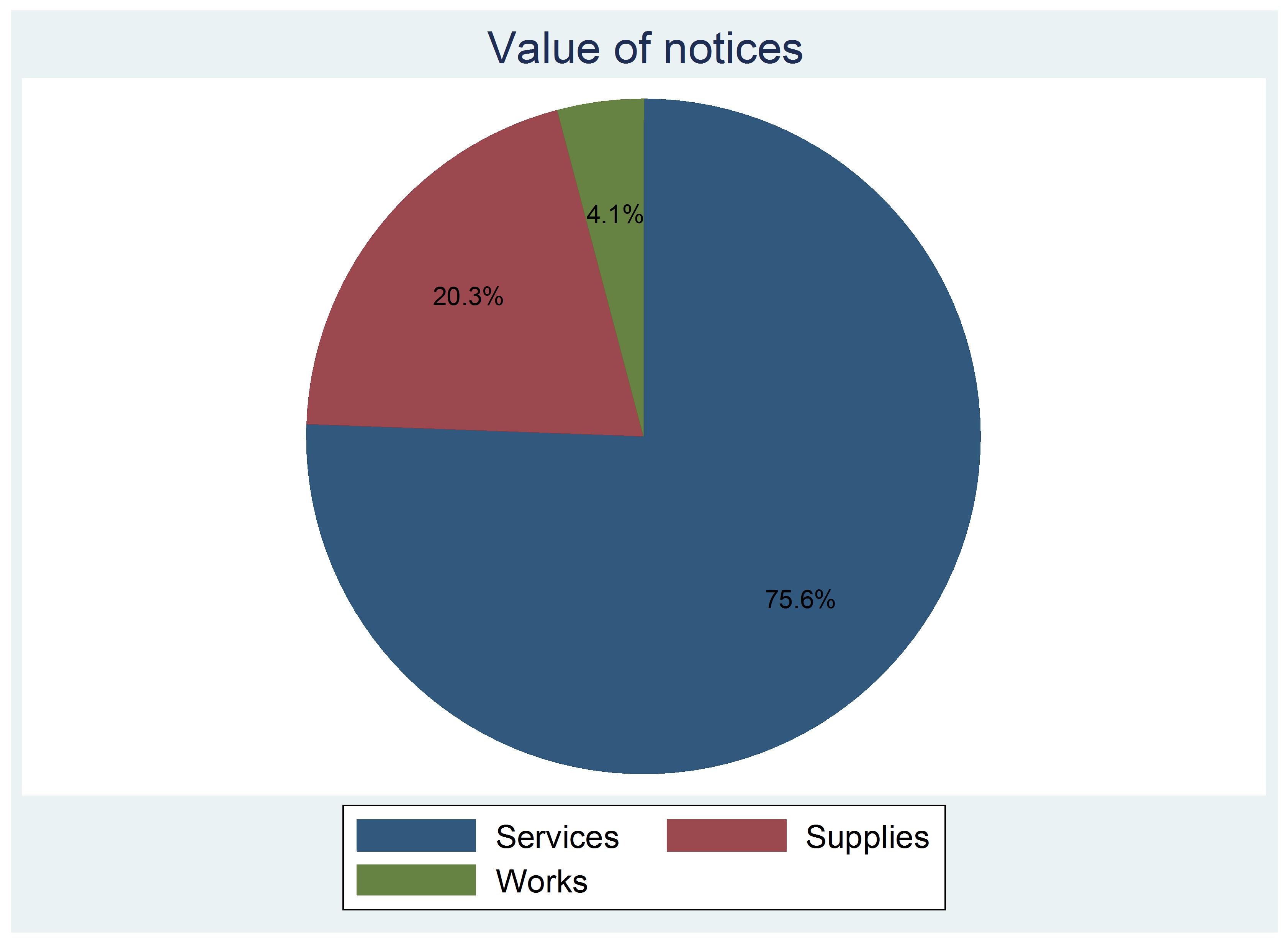

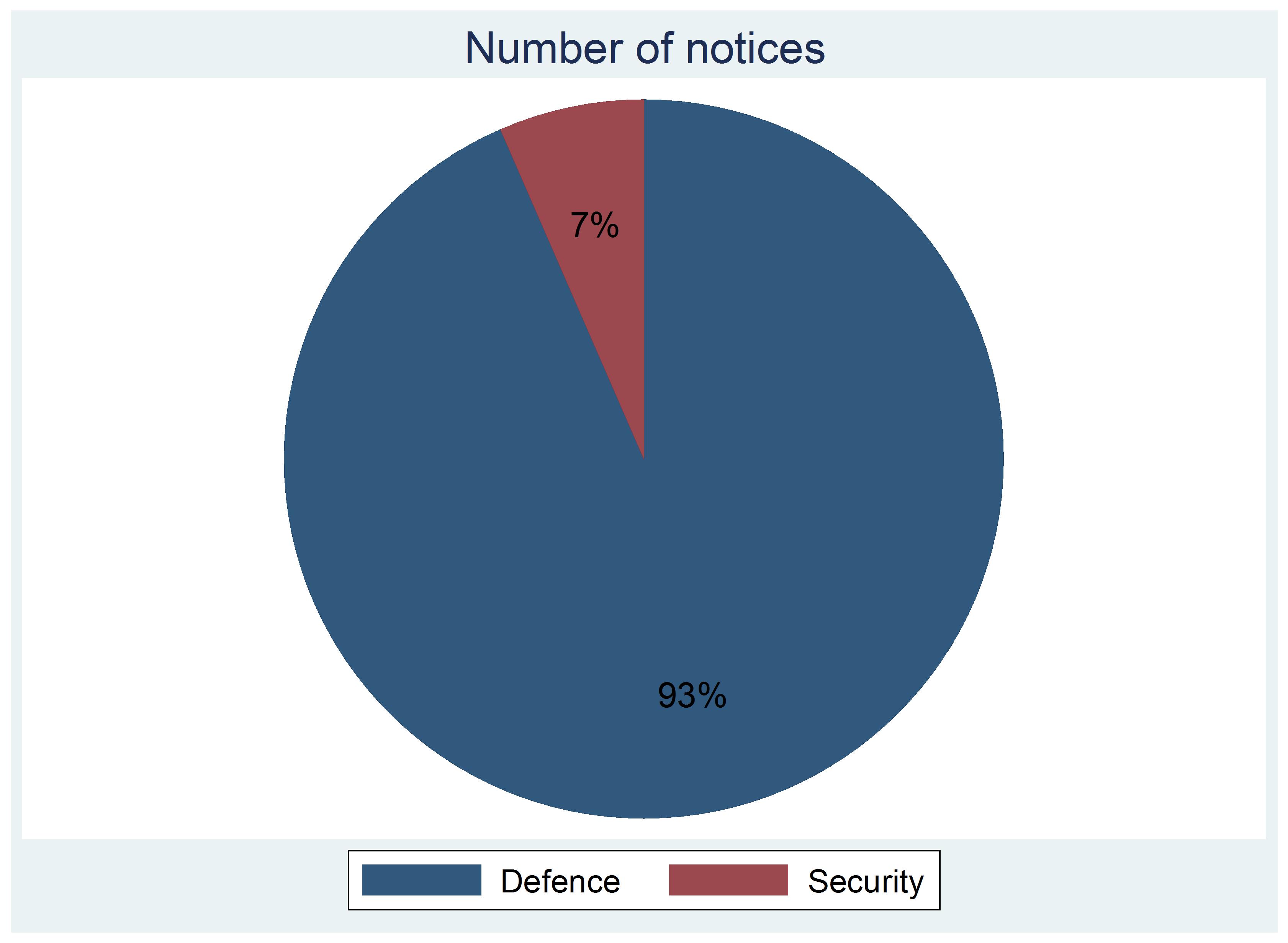

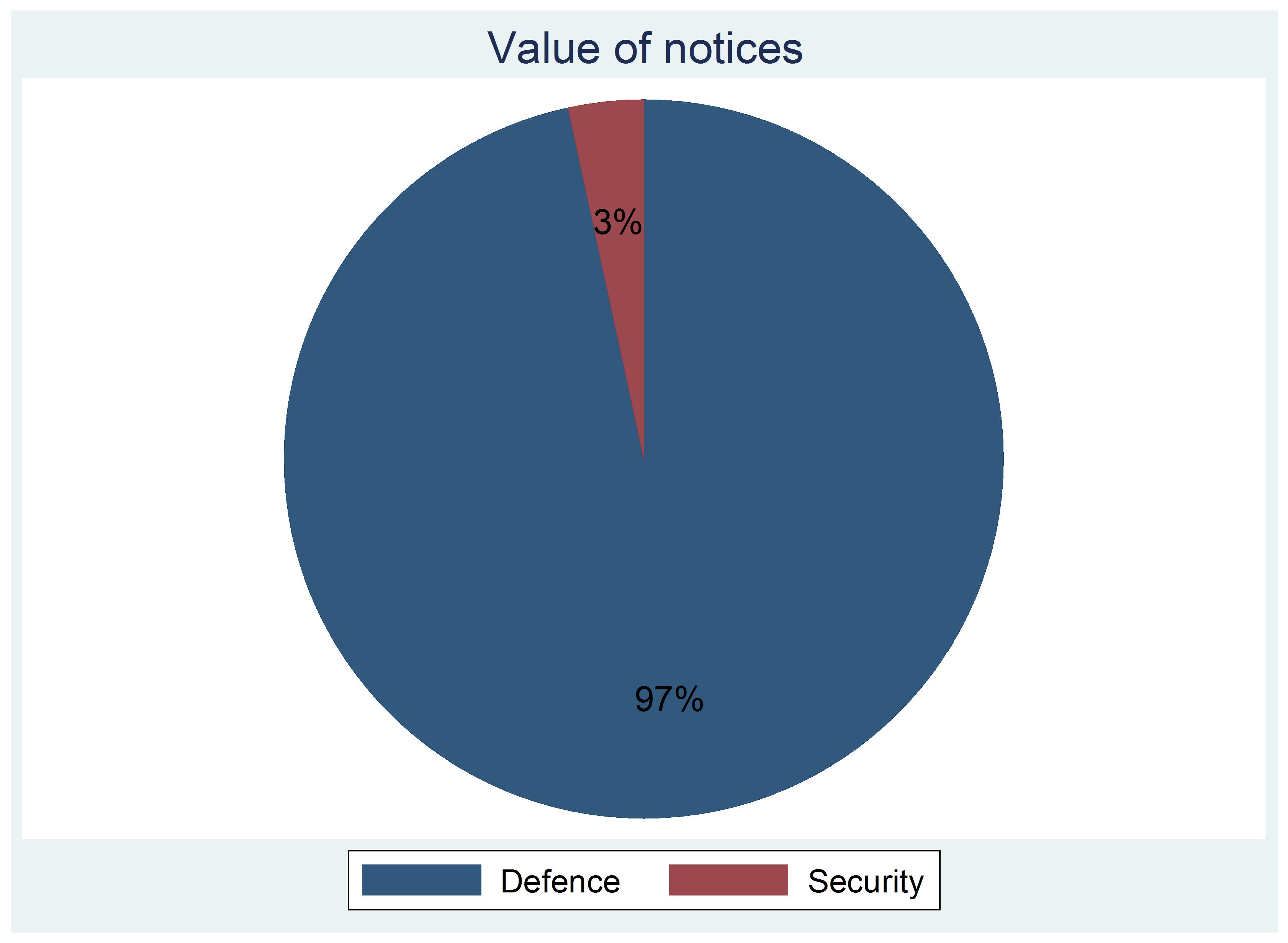

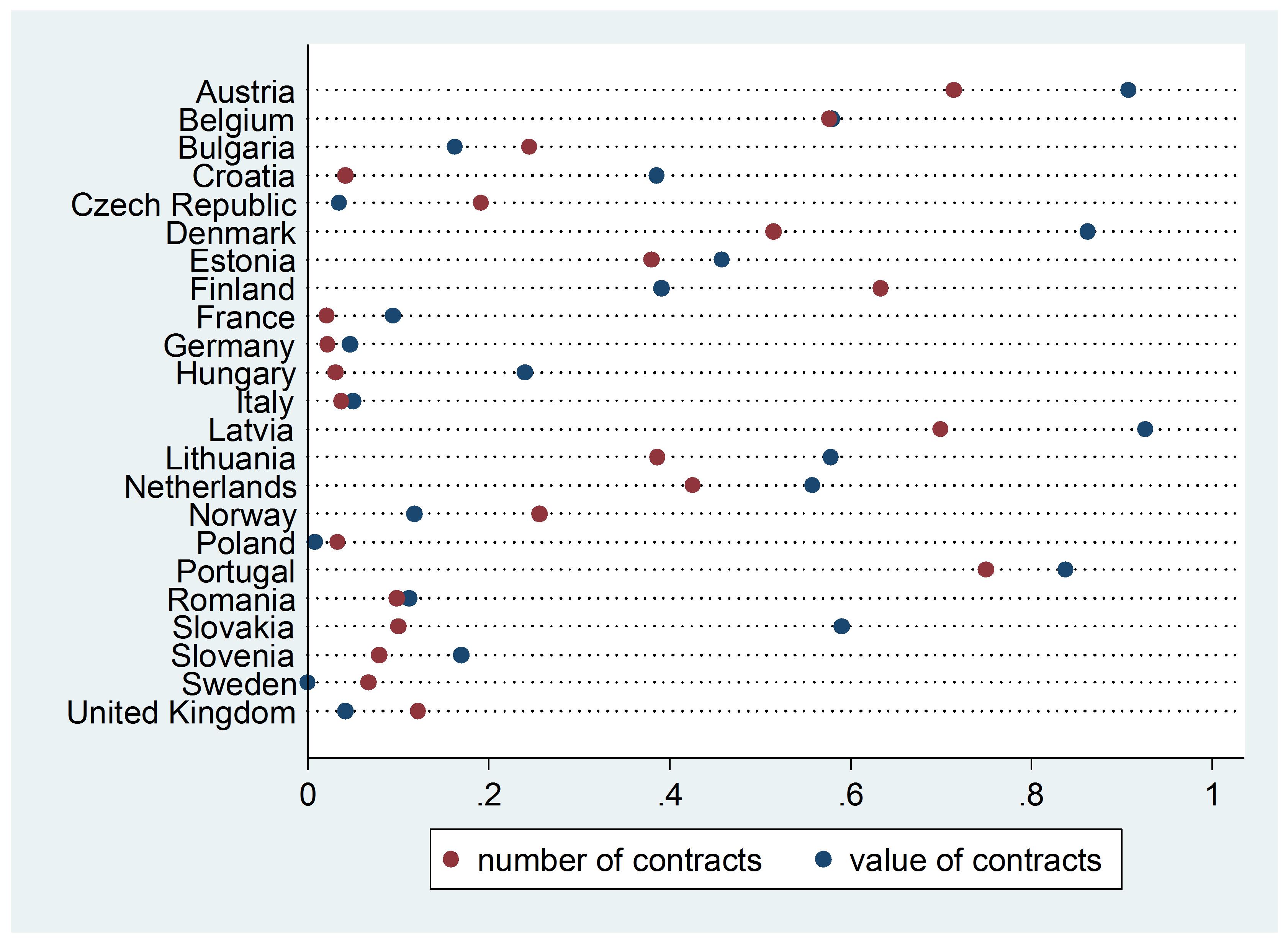

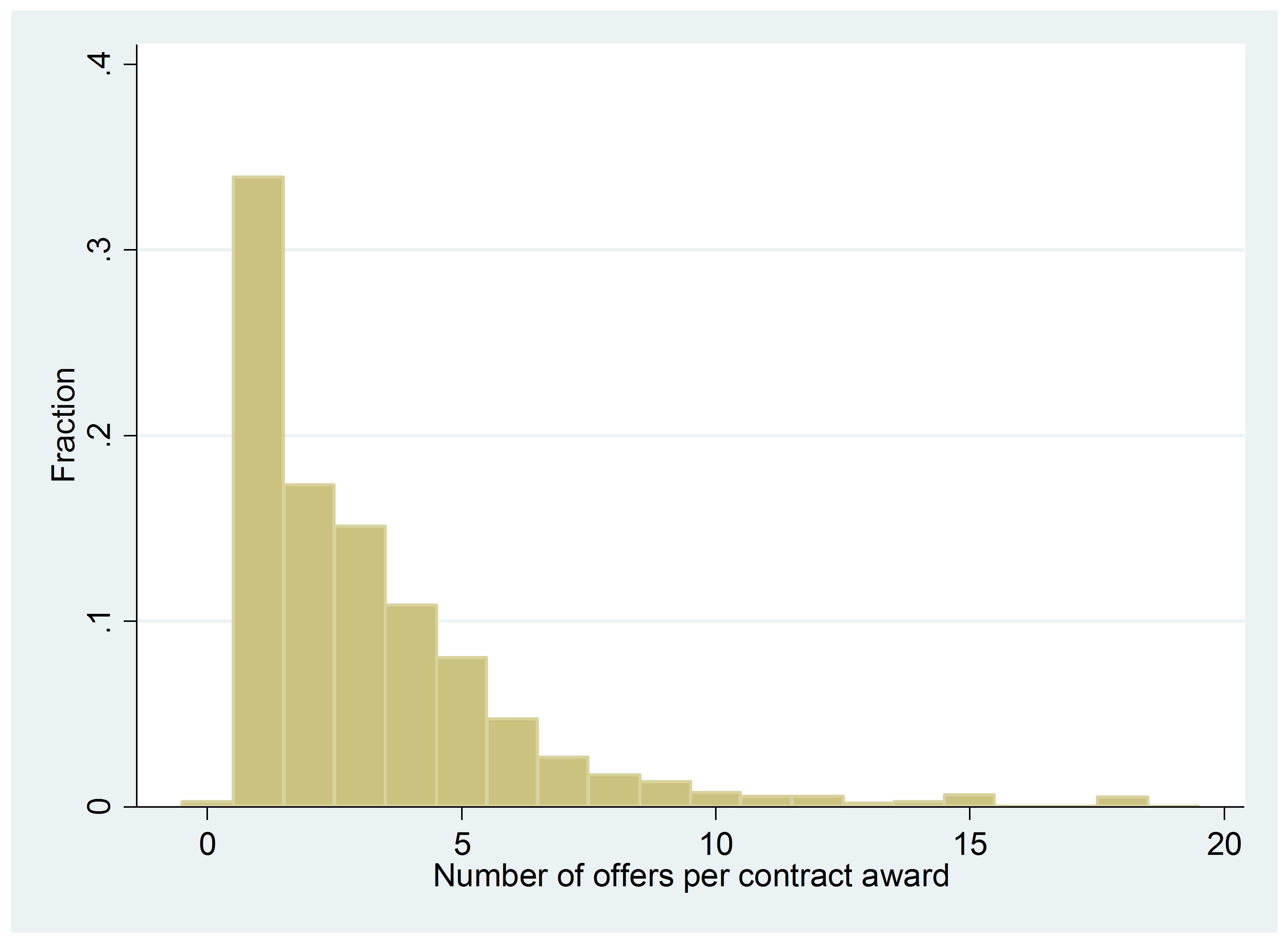

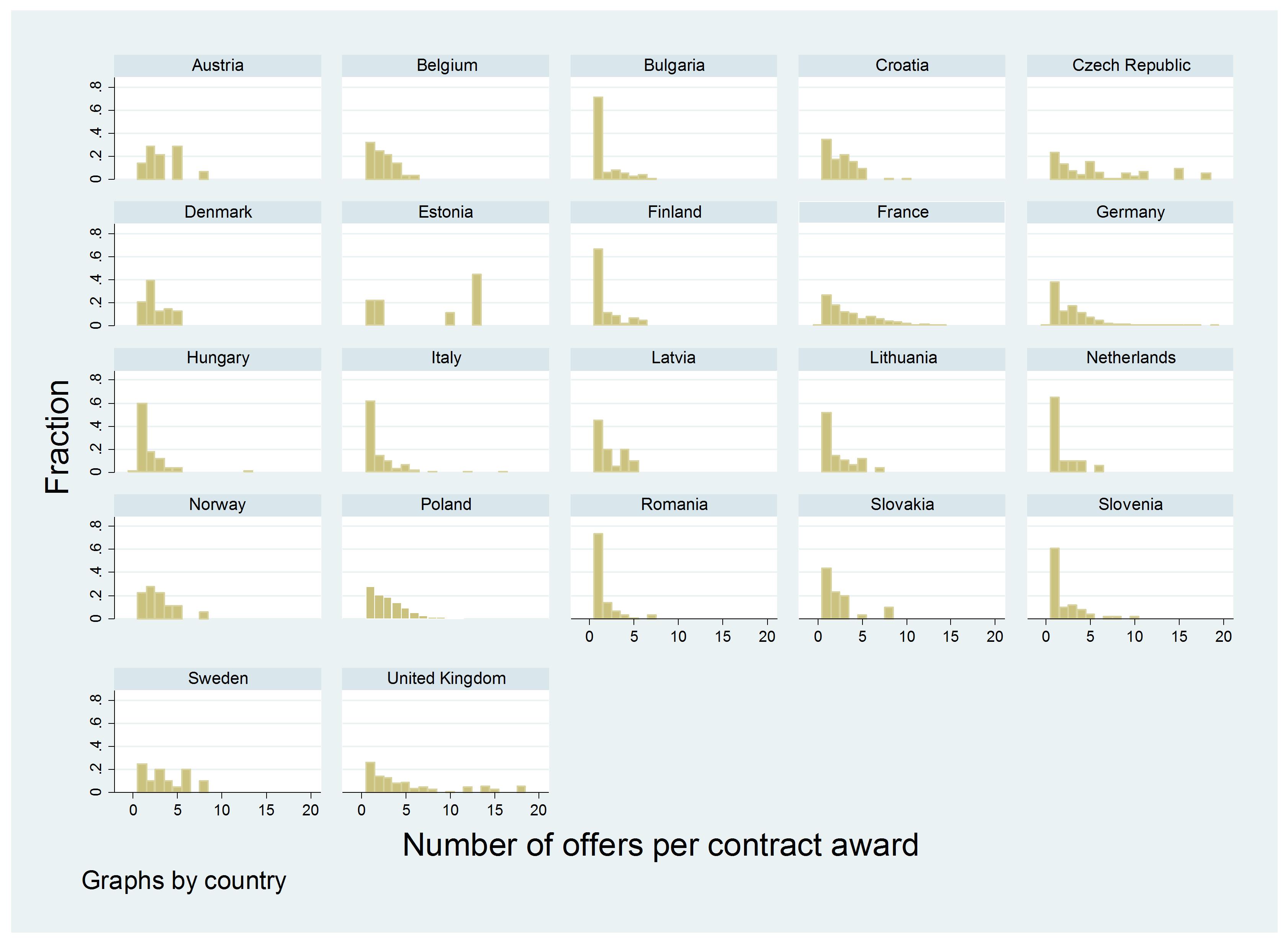

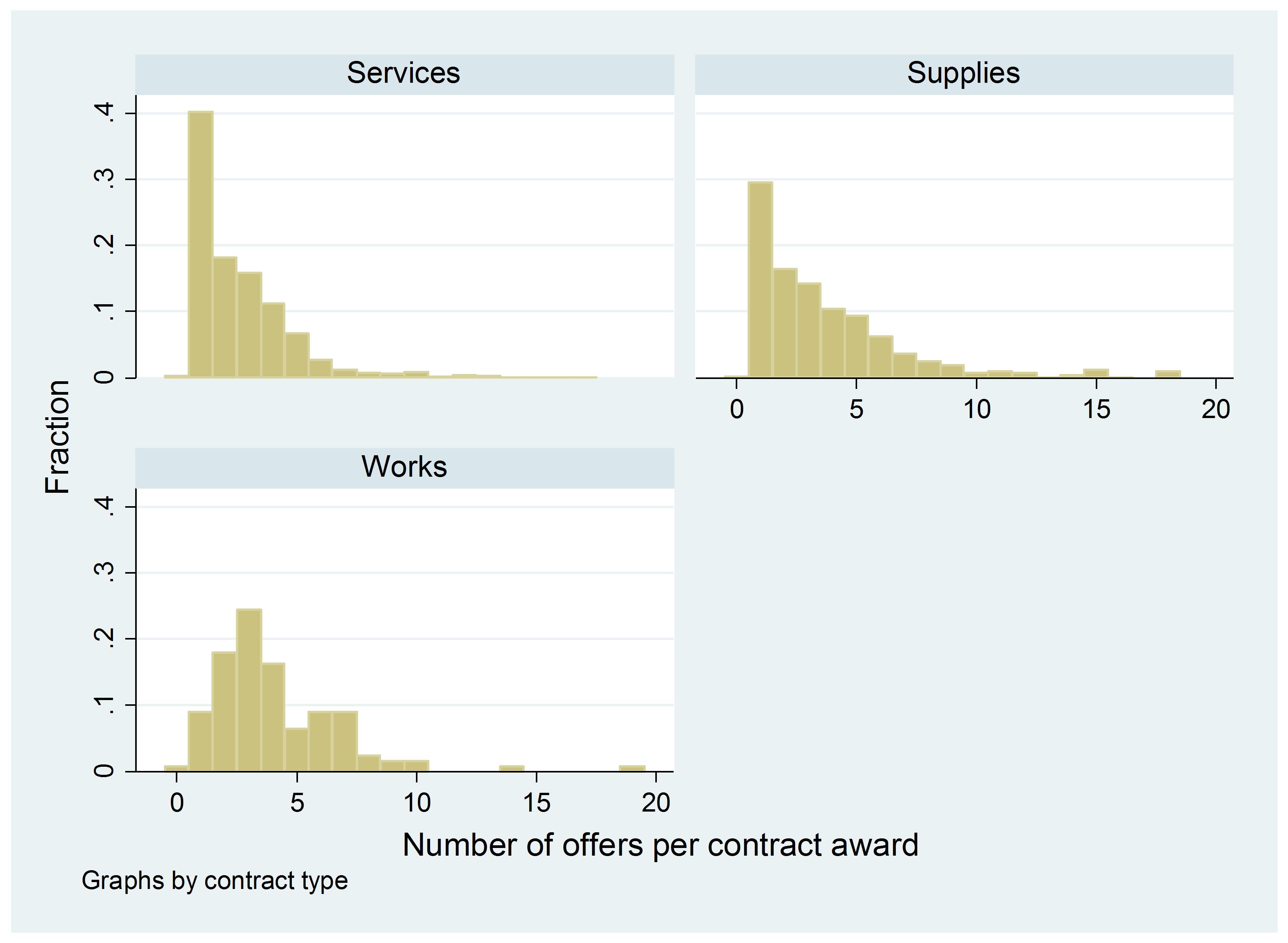

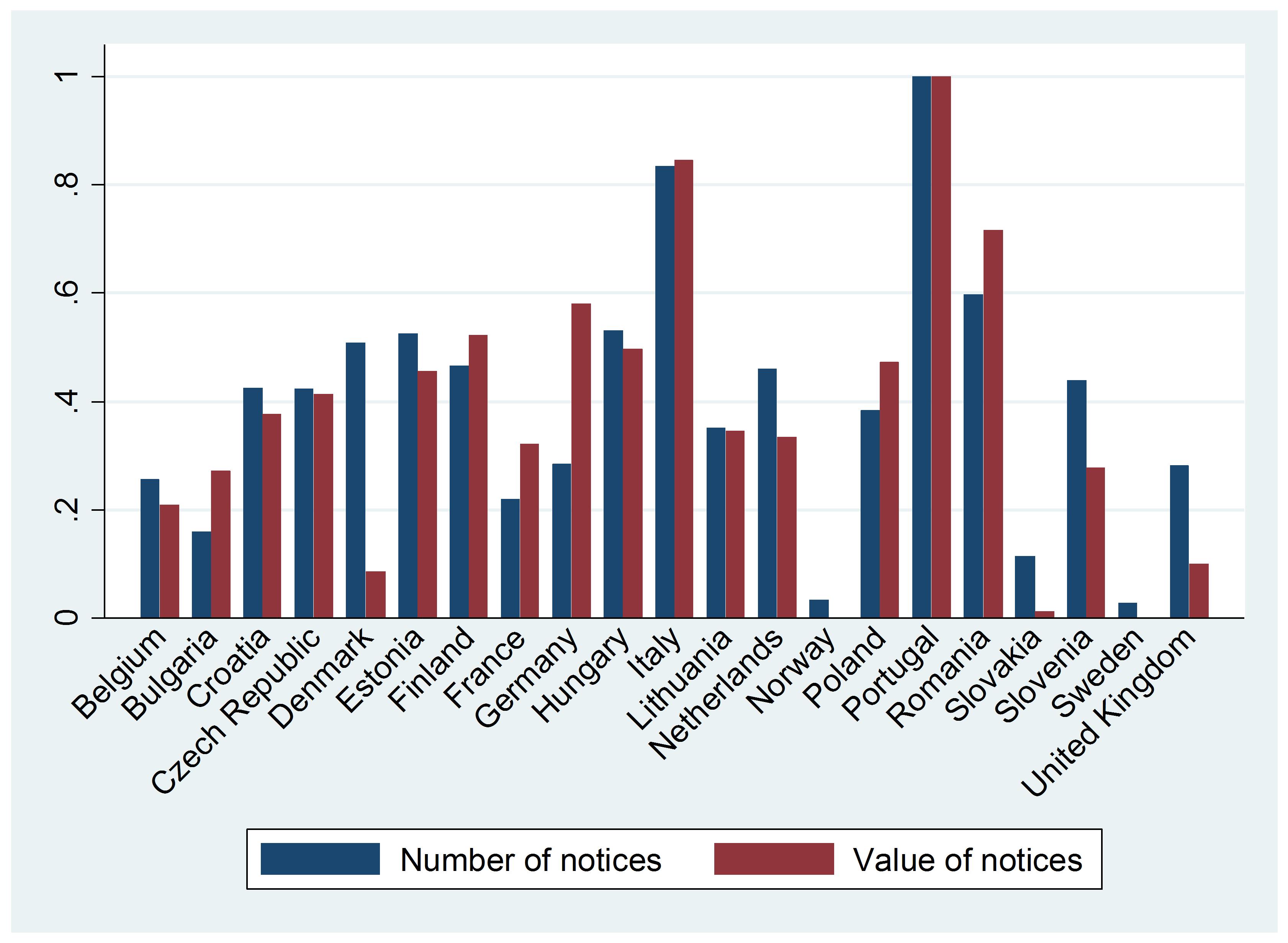

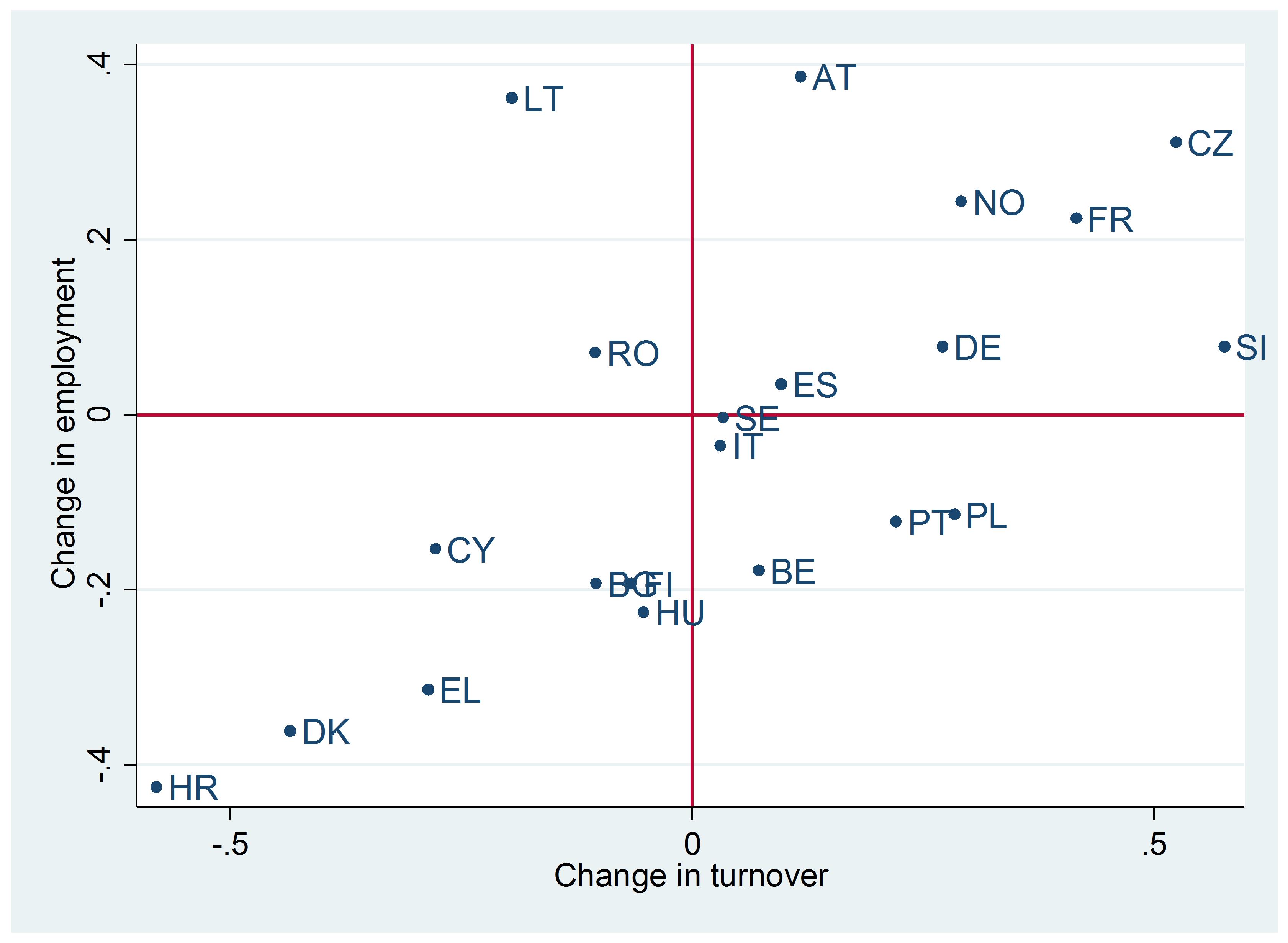

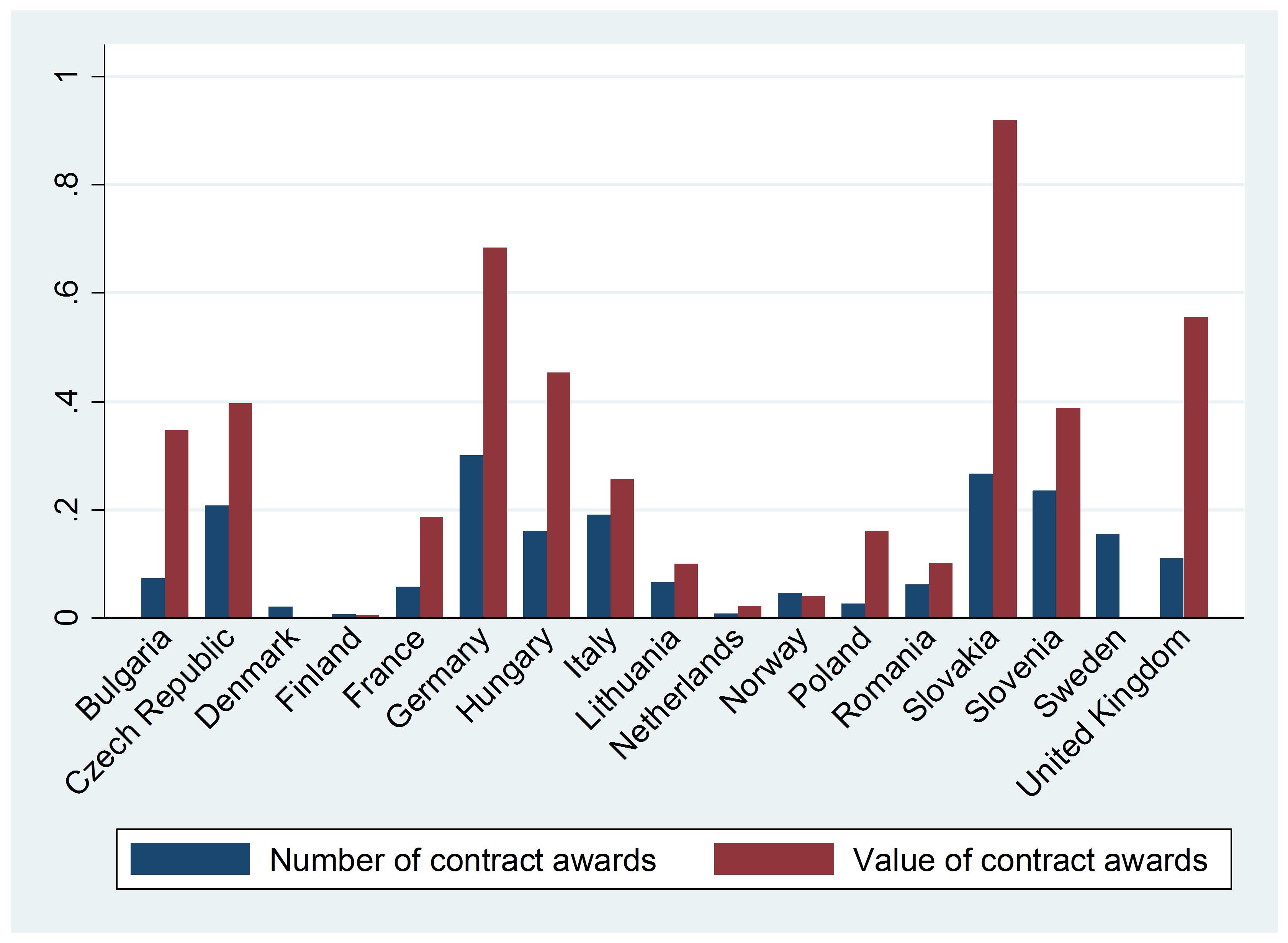

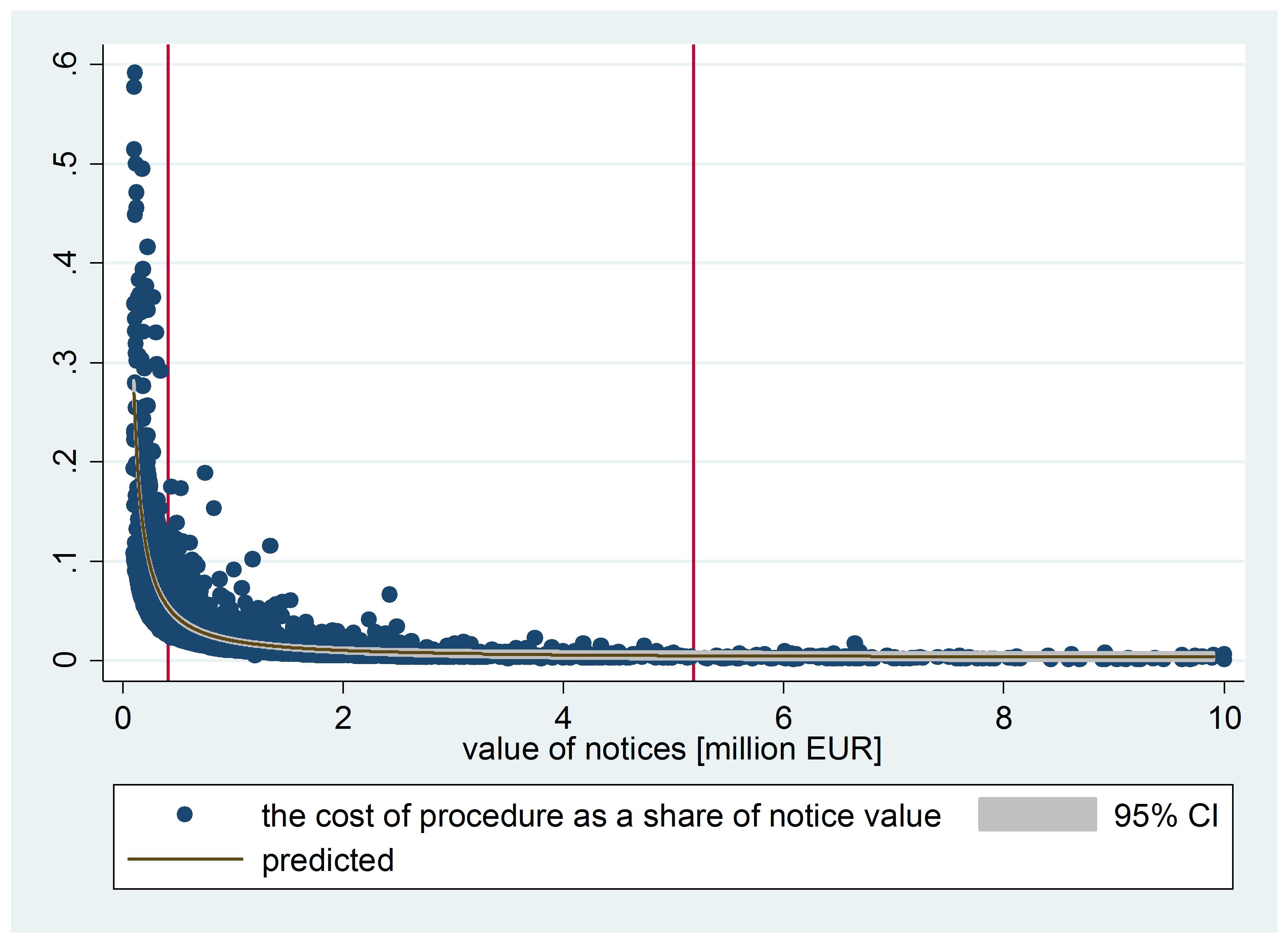

The examples of selected high value published under the Directive are provided in Table 9 overleaf.